Just about everyone has heard about gentrification: a phenomenon where a neighborhood that used to be middle-class or even poor gets a new influx of newcomers, changing the social makeup of the area. It is associated with increase in rents and housing prices. However, it's important to note that in general, the rich will not be satisfied with the housing of the poor, they will demand housing which, in size, quality and amenities, fit their desires in term of housing. Though high-rise condo towers are often the poster child of gentrification, gentrification also occurs in low-density areas when the area becomes desirable. It's the phenomenon of the "monster home" for example, where an old house is torn down to be replaced with a house as large as zoning allows:

|

| In Vancouver, older houses to the right, monster house to the left |

Though tearing down housing and replacing them is what a lot of people think when they think of gentrification (shiny high-rise towers have quite a psychological effect), much gentrification occurs in a very different manner, through renovations of buildings, merging units (duplexes being converted to "cottages" is a common case in Montréal), adding extensions, digging basements, etc... In fact, gentrification can very well occur without leaving any mark visible from the street, some renovations are so thorough that essentially all that's left of the old building is the exterior walls, and thus affordable apartments are turned into luxury apartments.

But there is another phenomenon where higher class housing deteriorates and becomes less desirable over time, allowing people of lower socio-economic status to be able to afford it. This is what is known as "filtering". This may be somewhat shocking to learn for some as it's not what we hear about in general. Still, it has been seen, for example in Japan where old housing tends to be significantly cheaper than new housing, for instance, this 70-square-meter (760-square-foot) condo apartment, or "mansion" as the Japanese say, built in 1969 sitting right on top of a subway station at 15 minutes from Shinjuku station is being sold for the equivalent of 230 000$ (searches for recent condos of similar sizes reveal that prices start at 550 000$ for ones built within the past 5 years), or in places like Kansas City, MO where there are plenty of turn-of-the-century (well, early 20th century) houses selling for extremely low prices.

Why do some places see gentrification while others see filtering? Can we get housing to start filtering instead to sate our needs for affordable housing?

Well, new cars have warranties, old cars don't... but that's the case for housing too in general, new homes tend to be covered by warranties offered by the home builder (sometimes required by law).

Well, cars' likelihood of breaking down increases over time... but so do houses, over time they will also require renovations and replacement of certain parts (the roof for instance).

So why are old cars worth less than new cars? Even cars that have been well-maintained, covered by extended warranties and in perfect condition are worth less than new cars.

I think the reason is that old cars have to compete with new cars, and it is extraordinarily rare that a new model is not better in some ways than an older model. The engine and transmission may be better, more fuel-efficient and/or powerful. The design may be more modern and more comfortable. More amenities may be added to the car, etc, etc... Car manufacturers don't really have a choice, their cars must compete not just with other brands' cars, but also with their older model.

Considering that, why would anyone be willing to pay more for an old car than a new car when new cars are often so objectively better?

That's why old cars see their value go down over time, because we keep building new cars and these cars keep getting better and better. We could theoretically keep old cars around and just upgrade them, change the engine, change the transmission, redo the interior, etc... That way we could insert new technologies in older vehicles, but it's considered too much of a bother versus buying new cars instead, that come with all this new technology right out of the car dealer's parking lot.

But imagine if we suddenly decided "we have too many cars already, let's put a quota on the amount of new cars we can build, or even ban making new cars altogether". Suddenly, because you have no influx of new cars on the market and you're stuck with the old cars, their value would cease going down, because they have no more competition from new cars. In that context, if something breaks on a car, people will fix it instead of scrapping it, and people may start replacing old engines with new ones instead of buying new cars.

Since new cars couldn't be built, it would also mean that the supply of cars in the market would be stagnant, if population and wealth is growing, it would mean that cars' value would get higher and higher all the time and a smaller and smaller share of the population would be able to afford them.

This is not merely theoretical, it has happened in real life. After the Cuban Revolution, the United States started an embargo on Cuba, which included, of course, cars. The USSR struggled to build enough cars for its own people, so it couldn't pick up the slack from the loss of access to American cars. Cuba itself had no car-making industry. The result was that the stream of cars dwindled to nearly nothing in Cuba. Without the ability to replace existing cars, Cubans have developed an expertise in keeping their old 50s-era American cars on the streets, repairing and replacing parts as they failed, decades after most of the cars' "brothers" have been scrapped as useless junk in the United States.

Whereas the car market in North America is a classic example of "filtering", the market in Cuba might be much closer to "gentrification", with cars maintaining their value and upgrades the only way to get better cars.

Why do some places see gentrification while others see filtering? Can we get housing to start filtering instead to sate our needs for affordable housing?

Let's talk about cars...

I think this analogy is good to understand the dynamic behind these phenomena. Cars are a prime example of filtering, the new car sold at 20 000$ is perhaps worth 10 000$ or less 5 years later, even if it is a low-mileage car. In developed countries, the secondhand car market has been what allowed the poor to afford cars that they could never have bought new. Why is it that cars' value go down while houses' value are not supposed to actually go down?Well, new cars have warranties, old cars don't... but that's the case for housing too in general, new homes tend to be covered by warranties offered by the home builder (sometimes required by law).

Well, cars' likelihood of breaking down increases over time... but so do houses, over time they will also require renovations and replacement of certain parts (the roof for instance).

So why are old cars worth less than new cars? Even cars that have been well-maintained, covered by extended warranties and in perfect condition are worth less than new cars.

I think the reason is that old cars have to compete with new cars, and it is extraordinarily rare that a new model is not better in some ways than an older model. The engine and transmission may be better, more fuel-efficient and/or powerful. The design may be more modern and more comfortable. More amenities may be added to the car, etc, etc... Car manufacturers don't really have a choice, their cars must compete not just with other brands' cars, but also with their older model.

Considering that, why would anyone be willing to pay more for an old car than a new car when new cars are often so objectively better?

That's why old cars see their value go down over time, because we keep building new cars and these cars keep getting better and better. We could theoretically keep old cars around and just upgrade them, change the engine, change the transmission, redo the interior, etc... That way we could insert new technologies in older vehicles, but it's considered too much of a bother versus buying new cars instead, that come with all this new technology right out of the car dealer's parking lot.

But imagine if we suddenly decided "we have too many cars already, let's put a quota on the amount of new cars we can build, or even ban making new cars altogether". Suddenly, because you have no influx of new cars on the market and you're stuck with the old cars, their value would cease going down, because they have no more competition from new cars. In that context, if something breaks on a car, people will fix it instead of scrapping it, and people may start replacing old engines with new ones instead of buying new cars.

Since new cars couldn't be built, it would also mean that the supply of cars in the market would be stagnant, if population and wealth is growing, it would mean that cars' value would get higher and higher all the time and a smaller and smaller share of the population would be able to afford them.

This is not merely theoretical, it has happened in real life. After the Cuban Revolution, the United States started an embargo on Cuba, which included, of course, cars. The USSR struggled to build enough cars for its own people, so it couldn't pick up the slack from the loss of access to American cars. Cuba itself had no car-making industry. The result was that the stream of cars dwindled to nearly nothing in Cuba. Without the ability to replace existing cars, Cubans have developed an expertise in keeping their old 50s-era American cars on the streets, repairing and replacing parts as they failed, decades after most of the cars' "brothers" have been scrapped as useless junk in the United States.

Whereas the car market in North America is a classic example of "filtering", the market in Cuba might be much closer to "gentrification", with cars maintaining their value and upgrades the only way to get better cars.

Now back to housing

In general, the North American market for housing is closer to the car market in Cuba, at least in urban housing. The unwillingness of communities to allow the replacement of old housing and the focus on preventing areas from evolving means that new housing can scarcely be built. Yes, they do manage to find ways to build a few new units, but not in any kind of quantity required to sate demand for housing. Since there is little competition from new constructions, people have to make do with old housing and renovations to upgrade them to a quality level people deem acceptable. What few new constructions exist often have distinctly higher prices, a sign that people are willing to pay more for modern housing that is generally better designed and better built (despite certain rants about supposed new "poor quality" condos... I've seen old apartments and new condos, there is no question for me that newer condos are significantly superior unless old apartments have actually been rebuilt from the ground up).

So without the ability to add enough new housing supply to satisfy the demand for housing, gentrification is the result. Old houses are repaired and upgraded rather than replaced. Growing populations and demand for urban housing means that by default some people have to be excluded from urban areas for lack of housing. Richer people buy older urban housing just to upgrade them through renovations, or through rebuilding, to make them fit their expectations.

On the other hand, filtering is sometimes seen in sprawling cities which have not yet hit the borders of their growth and where freeways and the destruction of density have made location much less important as there is little attractive location left. In this case, richer people will prefer buying new houses in new subdivisions built at the fringe of the city rather than older houses in older subdivisions. That's why new housing is still being built in cities with declining populations despite current housing stock being adequate to satisfy demand.

So the way to end gentrification and start the process of filtering is to allow for significant increases in supply for urban housing. This means not just allowing old building to be torn down and replaced, but allowing new constructions to be of higher density, to add housing supply. Destroying a house to build another house doesn't help. You can either build out (sprawl) or build up, and building out is not possible for built-out urban areas, even if you build new housing on the outskirts, as location matters, this housing will not reduce pressure in the urban area itself.

This means that even if all new constructions are luxury housing, it doesn't mean that people who aren't rich will not benefit from it. For instance, if you have a subway station in an area and rich people want to move there, preventing the construction of high-rise condos near the station is not helpful at all to prevent gentrification. Those people will just then buy currently affordable housing and renovate them into housing that fits their criteria. If you don't allow the rich to concentrate in new high-density housing, they will just spread out in lower-density areas and transform old housing into luxury housing instead.

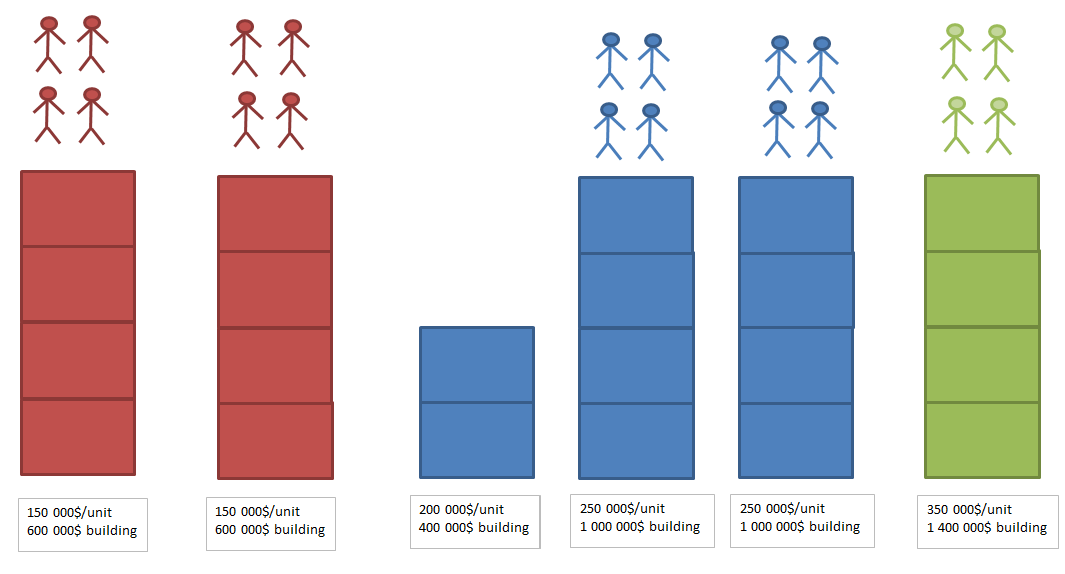

Let's make a simple representation of this concept. Here is an image representative of a mixed middle-class and poor neighborhood.

Here, each stick figure represents an household, each block an housing unit, the blocks are stacked to represent buildings. Red represents poor households and affordable housing units. Blue represents middle-class households and housing units. Green, which we will see in a moment, represents rich individuals and luxury housing units.

Now let's say the area becomes highly desirable, and rich people want to move in, and they want housing units that are worth 350 000$ or more and they tolerate high densities.

So here is one way they could be fitted in the current area, by replacement of a previous building with an higher, more luxurious bloc with more units. The building replaced will be a middle-class housing because it's more affordable to buy than the poor tenements as they have less units. Another middle-class building may also be replaced by an higher density middle-class building to welcome the previous occupants of the other building torn down to make way for the luxury housing building. The result would be this:

Here, density increased to allow everyone who wants to live in the area to do so. No one has been evicted from the area.

What happens if a promoter looks at this and says "Huh, so I can replace a middle-class building with an higher density middle-class building and make profits doing so? Then I will replace another of the 2-units building with a 4-unit building, which will attract the four remaining middle-class household not in high-density housing."? In essence, even more housing will be built. This will be the result:

Okay, so now the 2-unit middle-class housing is unoccupied, which means the owner will lose money on it and be willing to sell for a smaller price. This may draw out some of the poor households who can afford a somewhat more expensive, but higher quality, housing unit. I'll draw them in orange.

This is filtering, more precisely, the 2-unit middle-class building has just been filtered down and become more affordable. You have two unoccupied affordable housing units, which will create a pressure to keep prices down for affordable housing. Poor households move into middle-class housing units, that are a bit more expensive, but also higher quality than where they used to live.

But what happens if the NIMBYs and anti-gentrification activists who don't want rich people coming into the neighborhood come out and block the construction of higher buildings in the area by derailing zoning changes? Then the high-rise luxury building cannot be built. Will the rich leave, sad at being defeated? No, they won't, they will buy middle-class housing and renovate them to their taste. The middle-class people who lose their housing will in turn do the same to the poor people, taking over one of their buildings and renovating the units to be more pleasant for them. What happens to the poor who lose their affordable housing then? Well, they get kicked out of the neighborhood by lack of affordable housing. This is gentrification.

Alternatively, the rich could outright take over one of the affordable buildings, but housing size may be too small for them, and the end result is still the same, poor households get kicked out of the neighborhood.

Conclusion

What determines whether gentrification or filtering occurs is the amount of new housing that can be built. When enough housing can be built to satisfy new demand for housing, this will free up older housing units and allow their value to fall and become affordable for other people. The only way for old housing to filter down and fall in value is to make sure that old housing has to compete with new housing, just like old cars have to compete with new cars.

I've said it before, but it deserves repeating: limiting density and the construction of new housing supply brings about gentrification. On the other hand, succeeding in building more housing than the strict minimum required to accommodate newcomers will achieve filtering, as the more attractive housing draws rich and middle-class people, the vacated luxury or middle-class housing will fall in value to be affordable for people of a lower socio-economic class.

I wonder how many people would actually understand that fighting gentrification doesn't actually work, and even makes it worse as you've said. It's fascinating and makes complete sense when you think about it. It seems like the only thing one can do to prevent gentrification is to make absolutely sure the neighborhood sucks as much as possible, whether that's through crime, noise, pollution, unsavory characters, whatever. What a winning strategy huh?

ReplyDeleteOne point that was brought up over at Pedestrian Observations http://pedestrianobservations.wordpress.com/2014/09/03/dispersing-expensive-centers-edge-city-version-2/ is the idea of induced demand:

"In the US, the marginal additional building may actually displace poor people, if no new construction is allowed, simply by removing low-income apartments. It may even create local demand for high-income housing, for example by signaling that the neighborhood has improved. In San Francisco, this is compounded by the tech shuttles, as a critical mass of Silicon Valley-bound residents can justify running shuttles, creating demand for more high-income housing."

An interesting thought on the subject, but I still don't think it justifies limiting construction and redevelopment.

There may be some induced demand because of perceived neighborhood improvement at first, yes, especially since there is a large pent up demand for urban housing. But I think this is part of the pain of removing a band-aid fast, over time, it will likely balance itself when neighborhoods will all overall be perceived as improving due to the arrival of new housing and new businesses. The dynamic of induced demand in housing is generally an issue when the number of places where development can occur is really low, which bring very intense attention to the few places that allow it. If you allow developments in a wide range of areas at once, then the pressure on each place is much lessened.

DeleteI mean, if you upzone, or show willingness to upzone, only one place, then all developers will flock to it. If you show willingness to upzone plenty of neighborhoods, then developers will spread amongst them and so there will be less developers per neighborhood.

How much gentrification happens because governments want real estate prices to rise? This can either be to make the balance sheets of the banks look better, or to encourage more consumer spending funded by homeowners borrowing against the now-increased value of their properties. (It has been estimated that both the UK and USA were have been in recession for most of the time period since 2000, once the MEWing component of GDP was subtracted out.)

ReplyDeleteThank for your comment.

DeleteI don't think this is the result of intentional government policy. National governments have tried to motivate the real estate sector to support the economy in the past years, yes. However, I think many of these policies were just macro policies of lowering interest rates and getting credit to flow to support the economy, with little thought as to what form this would take in the economy. National governments have also been known to try to lower house values if they deem them too high, for instance the Canadian government has tightened access to credit many times to try to stop ballooning house prices in Vancouver and Toronto.

Furthermore, this dynamic that I describe typically occurs at a whole other level. It isn't national governments who mandate zoning to prevent higher densities. Quite the opposite, it is quite frequent, at least in recent years, that national governments' interventions in urban planning is to push for more density and for less restrictions on new constructions in built-up areas. It is local governments who make zoning and keep restrictions on housing supply, and local governments tend not to care much about GDP or the like, they care about getting the few motivated voters they have on their side, because it doesn't take much for mayors and councilors to lose elections, they just have to anger a few dozen people and they can be toast, since municipal elections have so little participation. Local voters tend to view any change on their neighborhood as bad, the people who would benefit from these developments are not current residents and so have no say in discussions on whether they should be allowed or not. I've described my understanding of this dynamic in another article:

http://urbankchoze.blogspot.com/2014/04/zonings-self-defense-mechanism-when.html

So since national governments are the ones controlling macroeconomic policy but that it's municipal government who use zoning to prevent density from increasing and lead to a rise in housing prices, I don't think it's an intentional objective of policy, it's just the logical conclusion of two different levels of government who have different objectives which have an unintentional side effect of causing gentrification and higher housing prices: national governments who tried to make credit access easier to increase demand on real estate and incite more construction to prop up the GDP, while municipal governments respond to their voters' NIMBY concerns by capping housing supply, leading to higher house prices.

This is spot-on and now has research to support it:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/blog/real-estate/2015/09/mission-moratorium-wont-help-affordable-housing.html