First of all, I've been on a trip to Japan for the past two weeks, expect even more observations on Japan than usual.

Now, let's talk about bikes. A beloved mode of transport for a lot of urbanists, as they constitute a much needed middle ground between pedestrians and cars. Like pedestrians, cyclists require no fuel other than muscle power, have no emissions and require very little infrastructure. They are however quite a bit faster, 2 to 4 times faster than a walk, depending on circumstances, making them sometimes nearly as fast as cars on certain city streets, and often faster than buses. They share some of the disadvantages of cars, but in more moderate forms, they do take quite a bit more space than pedestrians, especially in movement, and they need parking of some kind at their destination, just like cars.

Now, the average urban street in North America has two separate parts: the street, intended for motorized vehicles, and the sidewalk, intended for pedestrians. Where do cyclists fit in all this? There are three schools of thought I know of.

Vehicular cycling: the bike as a car

Vehicular cycling is basically exactly what it says on the box. It is about treating cyclists like another vehicle on the street, albeit a slow vehicle (like those tractors in rural areas) which are demanded to stick to the shoulder. So a cyclist's place is among the cars on the street, sharing the same surface. This is essentially what the laws say about cyclists, who are excluded from using sidewalks and told to stay on the street, at the extremity of the rightmost moving lane. Cyclists must be ready to impose their presence on cars, notably by moving to the center of moving lanes if needed for safety and by doing left turns in intersections.

|

| Taking the lane: a cyclist approaches a zone with parked cars, note how he keeps to the right to let cars pass him |

|

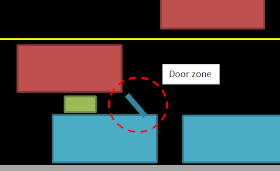

| If the cyclist tries to leave enough space to the car to pass him, he will be squeezed between moving and parked cars, in the door zone, a dangerous place indeed |

|

| "Taking the lane" means moving to the center of the lane, not giving space to the car behind to pass, avoiding being squeezed out but forcing cars to slow down |

The logic for this is that cyclists benefit from the same smooth pavement as cars and streets represent by far the greatest amount of the public right-of-way currently available. Vehicular cycling also maximizes speed, by acting like cars, cyclists end up benefiting from the smooth movements they are allowed on the street, for instance left turns instead of doing two street crossings.

Vehicular cycling may be safe for cyclists who are willing to stare down cars and who are able to maintain a fast speed, but it is well-known that many cyclists shirk away from it. Going in the path of a car to prevent it from passing you may be logical, but it assumes the driver will act responsibly, and if he doesn't, there is no denying the unique vulnerability of cyclists on the street, surrounded by moving tons of steel. Safety on streets also tend to depend on the speed differential between users, the greater it is, the more likely accidents will occur. So, to be safe, the ideal would be for cyclists and cars to go at the same speed, of course, this is ludicrous in most instances, but professional and sporting cyclists can achieve something close to it on urban streets.

So risk-adverse cyclists and cyclists who can't maintain high speeds tend to opt out of biking when vehicular cycling is the norm.

In terms of infrastructure, vehicular cycling requires little to none. All it requires is that lanes be made wide enough to allow cars to pass cyclists safely or to have shoulders, even on urban streets without parking. Since cars can be 2,1 meter wide (7 feet), assuming a safe passing margin of 1 meter (3 feet, more or less, which is regulatory in some places) and a cyclist's width of about 0,6 meter (2 feet), that means that the rightmost lane ought to be at least 3,7 meter wide (12 feet)... Which is a standard highway lane, exactly the kind of wide lanes we do not want in urban areas as they incite speeding, and that's assuming both cyclist and car are as far as possible from one another, with no margin between the lane's ends and the car and cyclist. If you consider trucks and buses, which can be 2,5 meter wide (a bit over 8 feet), you're up to 4,1 meters (nearly 14 feet). That's even worse.

You can provide a shoulder of 2 meters instead (a bit under 7 feet), but such shoulders do nothing to stop the problems of large lanes. They also incite cars to use them as parking, and once a car is parked in the shoulder, you have the same space problem as before, if not worse because then cyclists are cycling next to a steel wall.

So vehicular cycling actually requires wide lanes, which goes in contradiction to everything else we want in cities. They make crossing streets longer for pedestrians, incite speeding, reduce density, create large gaps between buildings, etc...

Bike segregation: creating a third part of the street

This is the approach most popular in urbanist circles in Europe and North America from what I see. The idea is that cyclists are not cars for obvious reasons: they are much more vulnerable and cannot go as fast as cars, so they need their own path separate from other users. This path should ideally be physically separated, but not necessarily, simple marking can suffice, especially on streets with less traffic.

|

| Physically separated bike path in Montréal |

|

| Bike lanes in Montréal |

By providing cyclists with space that is reserved to them, the goal is not only to allow them to travel around more safely by keeping cars away from them, but also to encourage more people to bike by providing a feeling of safety, a message that they belong there. All of this while maintaining a high speed. In fact, to provide high-speed, high-capacity bike links, segregated facilities are best.

The main issues with separated facilities is that they require quite a bit of space, especially if they are to be done well, and doing them well seems to be very hard to do. For example, take a look at this bike lane, from Montréal:

Do you see the problem? The bike lane encourages cyclists to travel pretty close to the parked cars, in or near the dooring zone. Ideally, there should be a buffer between the bike lane and the parked cars, to provide a buffer, either like this:

or like this:

Not only is this quite wide, but this doesn't eliminate all the problems. In the first case, cars that are parking will block the bike lane, in the second, bikes are only poorly visible from the street, which can cause problem at intersections.

So though separated facilities can be great, they can also create certain problems and require a lot of space to do well. If a street is wide enough to accommodate physically segregated bike lanes in a safe manner, that's good, otherwise, it's not always possible to get a great bike lane. This results in many cities, even pro-cycling ones like Vancouver and Montréal, to have big gaps in the bike lane network, with one kilometer and more between bike lanes and many commercial arterials lacking facilities as the streets are considered too narrow and/or the parking on them is judged as essential to the vitality of the street.

The pedestrian cyclist

The third approach is one that considers cyclists as pedestrians rather than as cars, telling them to ride on the sidewalk. This is quite rare in North America, but it is the rule, in practice if not under the law, in Japan.

|

| Crosswalk including a section for bikes in Tokyo |

Of course, the sidewalk as conceived in North America, made up of narrow segmented concrete blocks that are often not level with each other and with frequent curb cuts, is not appropriate at all for biking on. The cracks between the concrete blocks will provide quite a rough ride to any cyclist riding on them, the frequent ups and downs of curb cuts will challenge their ability to maintain a straight path and the narrowness of the sidewalk means there is little margin for error and it is quite impossible for two cyclists to pass each other safely.

|

| Typical North American sidewalk, not somewhere you can comfortably bike |

On the other hand, Japan has very different sidewalks. First, in most residential areas, there is just no sidewalk, every road user is equal. But on large arterial roads, there are sidewalks, and here is what they look like:

|

| Sidewalk in Fujisawa, Tokyo suburb |

|

| Sidewalk in Ginza, Tokyo |

|

| Sidewalk in Shibuya/Harajuku |

|

| Sidewalk in Sapporo |

|

| Asphalt sidewalk in Sapporo |

|

| Another sidewalk in Sapporo |

First, sidewalks in Japan eschew the whole concrete block thing, they go for two kinds: some sort of very level cobblestone and asphalt. Both of which offer a smooth riding surface to cyclists. Also, they don't depend too much on curb height to protect pedestrians from cars, they use trees, fences and the like, even in the absence of such features, the sidewalk is often almost the same level as the street. Sometimes, the curb is very narrow, with sidewalk and street being at the same level, separated by an elevated curb a few inches wide. This means that curb cut are much less disturbing to people walking or biking on the sidewalk.

|

| Typical sidewalk in North America, narrow and with a curb cut and ramp affecting almost the entire sidewalk |

|

| One example of sidewalk in Japan, narrow elevated curb with a fence on it |

|

| Other type of sidewalk in Japan, curb less elevated, the curb ramp is much less felt |

(BTW, the yellow lines in the examples posted above are not separations between cyclists and pedestrians, but guide lines for the blind.)

Remember in the case of vehicular cycling that this justified making wider lanes for cars and/or adding shoulders on urban streets devoid of the need for them otherwise? This is the same thing, the presence of cyclists forces planners to arrange for wider sidewalks to be able to have cyclists passing pedestrians or other cyclists.

The result of this is not only that cyclists are protected from cars by benefiting from segregated paths, but as these paths are the sidewalks, it means the safe cycling network is extremely complete in Japan, as every street with sidewalks tend to allow bikes on sidewalks.

This isn't perfect though, there is some degree of friction between cyclists and pedestrians, but this results mainly in lower speeds for cyclists who bike at 10-15 km/h from what I've seen rather than 15-25 km/h in North America. The reason is that cyclists are just as vulnerable in a crash as pedestrians, if not more so, so they tend to be more careful. It seems to work well at inciting people to bike though:

|

| In front of a suburban mall in Sapporo |

|

| A sarariman biking in a business suit, where is the lycra?! |

After getting rid of my prejudice against biking on sidewalks, I must admit liking the simplicity of the Japanese system, in which cyclists add space to sidewalks rather than roads. This contributes to wide, comfortable sidewalks where curb ramps aren't felt much, if at all. It does mean that biking is slower and every sidewalk has less capacity than segregated bike paths or lanes, yet the high number of streets with sidewalks mean that high capacity isn't required, cyclists will distribute themselves amongst many possible routes and avoid congestion. However, this would require a complete redesign of sidewalks in North America to apply, biking on sidewalks as it is is not recommended at all.

If speed and high capacity are sought, segregated bike lanes are still unbeatable. However, vehicular cycling, though it may work well for individuals, should not be where we place our bets on how to develop cycling.

On newworldeconomics, it says that 85% of street-kilometers in Japanese cities are the single lane, no sidewalk type. Also it says that thinner lanes and no on-street parking is usual on the multi-lane arterials. Is that your experience, simval84?

ReplyDeleteI also wonder if there are any cyclists acting like vehicular cyclists on the smaller arterials. Most of your photos are 3+ lanes in each direction, but Google Earth shows a lot of one lane in each direction arterials. A cyclist could be comfortable there at 20-25 kmph if people drive like they do in North America.

In terms of kilometer of street, of course the narrow, no sidewalk, streets dominate, as there are a lot more of them, just like most streets in North America would be the relatively narrow residential street, not the wide highway. Well, at least in Tokyo and other old cities, Japan has very recent cities I'm planning to write about soon.

DeleteOn street parking is effectively very rare, and travel lanes are narrower even on arterials, I'd say about 3 meters wide (10 feet) on average, without any shoulder. So there's not a whole lot of space for cyclists to bike on the street, but a few cyclists still do it, they are rare however. I've seen a couple of lycra-wearing, road bike-riding cyclists, and they were on the street, not on the sidewalk.

Japanese drivers tend to be very mindful of pedestrians and cyclists and not aggressive like North American drivers, still, there's not much space for vehicular cycling due to the lack of shoulder and narrow streets. And most Japanese bikes are not built for speed but for comfort and utility. Japanese cyclists will sometimes bike on the street if there is little traffic and the sidewalks are narrower than usual, or if the pedestrian lights at intersections are too long (cyclists on the sidewalk respect the pedestrian signals at intersections, cyclists on the street respect the traffic lights for cars instead).

Any comment on the more sophisticated Dutch and Danish approaches for cycle tracks which fall between your descriptions of segregated cycling and pedestrian cycling? In technical terms it's segregated cycling, but rather than painted "bike lanes" which are something of a stopgap, they're neither "of the street" or "of the sidewalk" but a third "of their own" network.

ReplyDeleteIn this case there's two sets of curbs, one between the street and the cycle track, and another between the cycle track and the sidewalk. So it's a bit of a stair-stepped cross section, but with fairly small changes in elevation kind of like you see in Japan. Street trees, if present, exist as bump-outs into the parking lane, as do bus stops, while signs and parking meters and lamp posts are most often near the curb on the sidewalk, keeping the cycle track clear.

With the highest bike mode share of the western world, they seem to know what they're doing. Here's a good example of the Dutch approach, which is arguably more sophisticated and successful than the Danish approach, though it's more a case of the details (especially at intersections) than anything: http://goo.gl/maps/Vb5LW Either way we're a good 40 years behind on best practices here in North America, but sadly we seem unwilling to learn from these other countries.

I've never been to Denmark or Holland though I've certainly read about them and explored them on Google Maps. It is certainly a very sophisticated approach of bike segregation, a model for activists and planners in North America.

DeleteBut I don't think they are a separate approach, the three ones I see could be essentially:

Bikes share the space of cars

Bikes share the space of pedestrians

Bikes deserve their own space

The Dutch and Danish approaches are described much better elsewhere. This article of mine meant primarily to describe the Japanese approach as I saw it on my most recent trip there, which is an approach that is not common at all, or even considered, in North America and even on urbanist websites, where only bike segregation and vehicular cycling tend to be discussed.

As to mode share, the data I've seen shows that bike mode share in Japan can get up to 20-25% in certain cities, but walking itself tends to get another 15-25% share of transport. Which I think may say something about how Japanese cities are denser and more walking friendly than Dutch or Danish cities, which tend to be dense compared to American cities, but aren't all that dense, with plenty of green buffer zones and more segregated uses.

Fair enough. It's certainly evident that Japan and Asia in general have done well sticking with their "traditional cities" format that leads to exceptional walkability. Even Latin America seems to do this at least to some extent. Europe shows very clear demarcations between their medieval city centers and a more "hypertrophic" industrial-age development pattern surrounding them. At least they never went as crazy with it or let it devolve a disconnected suburban typology to the extent we did on this side of the pond.

DeleteI suspect that the walkability of Japan coupled with its crushingly overcrowded train systems actually hurts their bike mode share. Bikes don't lend themselves well to busy pedestrian-dominated streets, and if it's easy enough to walk then why bother? In many European countries they go to great lengths to provide bike parking and to allow room for bikes on trains. That's much more difficult in a place like Japan where there's so much less room.

There are some troubles with bike parking overspill in Japan, but it's mainly that people park their bikes where they bother people walking by or shopping, it's not really a lack of space as most Japanese are content to let their 150$ mamacharis unlocked to racks, simply with wheel locks. They do add parking space where needed, over there, I found:

Delete-Self-locking racks in front of supermarkets in Tokyo, free for 2 hours, then 100 yen (1$) per hour after that

-Shopping malls on the outskirts of Sapporo with hundreds of bicycles parked right near the entrance of it, in a large place set aside for them

-A 3-story bicycle parking garage near a train station in Chigasaki, a suburb of Tokyo, which could lead to bike mode share being underestimated as people coming by bike to the train station and then taking the train may be counted in surveys as doing a "rail" trip, when in fact it was multi-modal bike-rail.

I've taken pictures, but not posted them yet, I think I will do so now, a general article on biking in Japan. Keep an eye out on the blog.

@Jeffrey -- Indeed, bicycles are much more popular in slightly less dense (though still very dense by American standards) areas of Tokyo and its suburbs than in the very crowded commercial areas of central Tokyo.

DeleteBikes on trains are a complete non-starter, as it would significantly reduce capacity and increase boarding times. Because of the general layout of Tokyo it's not really necessary anyway, as almost all commercial destinations are within easy walking distance of a train station.

People use bikes for local trips around their home area, or as a means for getting to the train station. In the latter case, they park their bike there.