Urbanists often speak of density, I've written about why it is so important with regards to sustainable urban areas before. Density allows for services, businesses and jobs to be more in proximity to where people live, which makes motorized transport less of a requirement and more optional. But how to measure it? A traditional measure is the residential population by area, for example, people per square kilometer or square mile, or by hectare or acre. This measure has a big flaw: it counts only residential density, but what about jobs and commercial density? The downtown area in many cities all across the world is the most densely built area, yet by that measure, it would be of very low density because most buildings are not residential, and so few people actually inhabit the downtown area. One attempt to balance things out is to add jobs in an area to the residential population, thus you have a density of residents+jobs per area.

But the big problem with this measure is that it is quite hard to actually use that data in regulation and planning, because both people and businesses are free to move around, you can't compel X number of people or jobs to be in an area. You can only provide Y amount of buildings to allow them to be there, but people are ultimately free to settle there or not. And that is why we sometimes see alternative measures of density, especially in planning, like residential units per hectare or acre. So instead of counting people, you count dwelling units. However, this also has problems, because it's hard to include commercial areas in this measure. A single big box store can have millions of square feet of space, but it is just one commercial unit, so you obviously can't add this as one unit in that measure.

There is a measure of density which can be very helpful then, the Floor-Area ratio.

Floor-Area Ratio: agnostic measure of building density

The Floor-Area Ratio (FAR) is a ratio, so often a percentage, of the sum of the floorspace of buildings to the area of the lot. OK, let's do things with an example, let's take a 2-story house on a lot:

|

| Suburban 2-story house |

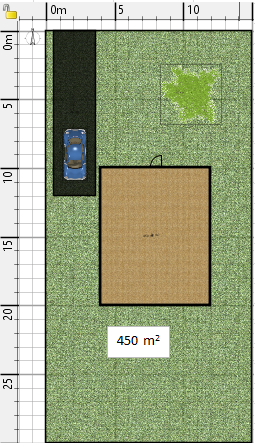

So, first, let's see what's the size of the lot on which it is built:

|

| Size of the lot |

So the lot is 450 square meter (1 square meter is roughly 10,7 square feet).

Now, let's see how big the ground floor is:

|

| The ground floor |

Now, let's look at the second floor, which isn't as big.

|

| The second floor |

OK, so the first floor is 80 square meters, the second is 66 square meters, for a total of 146 square meters.

So the FAR in this case is (80 m2+ 66 m2) divided by 450 m2, or 32,4%.

The attractiveness of the FAR is that it is use-agnostic and allows to compare residential, commercial and industrial buildings on an equal footing. It strictly calculates the density of the built area. It also doesn't care whether the developments are more "tower in the park" or "European traditional city block", it will tell you how much floor area people have to live or work in.

|

| A modernist tower versus traditional European city buildings, which do you perceive as denser: |

|

| ...the tightly-built 4-story buildings,... |

|

| ...or the stand-alone 8-story buildings? |

|

| Thanks to FAR, we know both are equally densely built |

Regulating FAR or not

So if FAR is use-agnostic and allows to compare the density of built areas, so it's a good measure of building density. However, should it bear the brunt of our planning regulations? Certain planning systems do already use it, France has used it for a long time, though it is phasing it out. Japanese zoning does use it even today. Many North American cities use it in their downtown areas.

But the important questions we should ask are: what do we really want to control? What are the impacts of decisions to regulate built areas in certain ways?

So is FAR really something we want to regulate directly? In general, I would say no, it isn't. There may be certain externalities to particularly dense developments like plunging areas into perpetual shadows or avoiding covering lots too much, causing major problems to sewers during rain, however, FAR is not the way to deal with those. For shadow-avoidance, height limits relative to the distance to the next lot are much more effective. For the reduction of surface runoff during rain, lot coverage limits are better. Of course, add these two limits together and you're essentially limiting FAR, but you're not limiting FAR directly, you're simply regulating certain forms to avoid problems, FAR just happens to be limited indirectly.

Oh, and if you want to limit traffic generated by developments... limit parking spots, not population. If you limit residential parking, then you limit how many cars there are to drive, if you limit commercial parking, then you limit how many people can go there in a car.

Oh, and if you want to limit traffic generated by developments... limit parking spots, not population. If you limit residential parking, then you limit how many cars there are to drive, if you limit commercial parking, then you limit how many people can go there in a car.

If there is one reason to regulate FAR, it is for economic reasons. The value of land being dependent on the density of revenue-producing building that can be built, restricting FAR can limit the value of land, which can be useful in certain cases. That is why I did refer to FAR limits in my post on incrementalism, as my focus was on the economics of urban developments. I focused on FAR to make sure that buildings that replace older ones are significantly denser to reduce the cost of replacing older buildings and allow newer, denser buildings to still be affordable. So in that case, my focus was the cost of construction of each square foot of living space. It is not an externality per se, just a way to control costs of land and housing within certain limits.

The impacts of certain building regulations

More importantly, I think we have to be cautious around building regulations, because these have important impacts that may not be apparently obvious.

For example, much has been written about Americans' ever-growing living quarters, bigger and bigger houses. Why is that? Well, this is a combination of minimum lot sizes, single-family only zoning and minimum off-street parking regulations, while at the same time Floor-Area Ratio is not directly limited in most suburban areas.

All these regulations in effect limit how many units per hectare (or acre) can be built. The strongest limit is the combination of lot sizes and single-family zoning, which means that you mandate a large lot (say 6 000 to 10 000 square foot) and you say only one housing unit can be built on it. Well, in that case, why wouldn't you build bigger and bigger housing units then? Up to what people can afford? If you build a small house on that lot, that is a waste of a lot, building smaller houses won't increase density and will reduce the profit margin of the developer. If there's no regulation to impose a smaller house, why build one?

Minimum parking regulations have a similar impact, in that the number of units that can be built will be dependent on the number of parking spots that can be built economically on the lot. For example, in Japan, you can see small buildings full of studio apartments like these a bit everywhere:

|

| Small studio apartments typical of Japan, rendered in Sweet Home 3D, 12 units on a 350-square meter lot (around 4 000 square feet), more than 300 units per hectare, FAR 70% |

These are possible because the minimum parking regulation are very low, I've heard that one parking spot per two apartments isn't rare, and regulations don't control much the number of units that can be built on a lot, there is no single-family zoning. So you can have a lot of very small apartments on a small single lot, yielding high densities of 200 units per hectare or more (80 per acre). Of course, these are very small, so fit only for one occupant, but even with just one occupant, that yields a population density of 20 000 people per square kilometer or more, or more than 50 000 per square mile. It also makes small, very cheap apartments easy to build anywhere, providing a cheap housing option for singles.

Now, why don't we have something like that in most North American cities? Well, because most towns have strict minimum parking regulations, some of which don't even differentiate 2-BR apartments from small studios and mandate 1,5 parking spots per apartment, no matter how big or small. So if we take this previous building and build 18 places of parking, what do we get?

|

| The previous studio apartment building but with typical North American off-street parking regulation, FAR 25% |

In this case, density is actually cut to a third as the lot is three times as large to accommodate the parking. In that context, what is the point of building that type of building? The revenues from the lot would be very low. It is much better then to build much bigger housing units, say 2-bedroom apartments, so that you can waste less of the lot for parking and get better revenues from it. For example, they could build something like this:

|

| Apartment building with 6 2-BR apartments, FAR 70%, 65 units per hectare |

This type of building is much more likely to be built in the North American regulatory context because you can get higher FAR, and it also has higher population density than the studios with 18 parking spots, because each unit will have 2 or 3 people in it.

An interesting point to consider is what happens to the single individuals in North America that seek cheap housing options, since they are largely deprived of the small 1-Bedroom apartments due to regulations restricting the number of units that can be built per area? Well, they share apartments with roommates. Indeed, becoming roommates is the way consumers have devised to go around the excessive parking and density limitations imposed by North American planners. It is not a desirable situation, but when in a pinch, people will do it.

So North American regulations that limit the density of units but are less restrictive on FAR will result in bigger housing units as developers will build big units to maximize profits.

Policies that do the opposite, meaning limit FAR but are favorable to subdividing buildings in many units thanks to a lack of minimum lot size and low or no minimum parking regulation will have the opposite effect: tend to increase housing density but reduce the size of units.

That is because, all else being equal, in general, the value of bigger housing units is greater than the value of smaller units, but the value PER SQUARE FOOT of smaller units tends to be higher than that of bigger units. So to maximize revenue, if the number of units is limited by regulation, then the bigger the units, the more revenue they will bring in. If on the other hand you limit the amount of square feet of floor developers can build but do not limit the number of units, then they will have a tendency to build more, smaller, units.

That is because, all else being equal, in general, the value of bigger housing units is greater than the value of smaller units, but the value PER SQUARE FOOT of smaller units tends to be higher than that of bigger units. So to maximize revenue, if the number of units is limited by regulation, then the bigger the units, the more revenue they will bring in. If on the other hand you limit the amount of square feet of floor developers can build but do not limit the number of units, then they will have a tendency to build more, smaller, units.

There are other impacts that follow other policies. For example, in certain cities, the height and/or number of stories of buildings will be limited, but basements do not count as a story, the result will be plenty of houses with basements and basement units (which I regard as an undesirable effect, especially in highly populated areas, no one wants to live in a basement and learn to tell people by their ankles).

If FAR is limited but balconies do not count, expect large balconies to happen.That is possibly what happened in Japan, as balconies in condos can be very large even when units are small. For example, here is a floorplan of a condo in Tokyo, found on Suumo.JP:

|

| This 70-square meter apartment has a balcony of nearly 13 square meter, nearly 16% of the floor is a balcony, but it doesn't count towards the FAR limit |

The United States represent an extreme of the dynamic of how limiting the density of housing units can yield bigger and bigger housing units. The opposite of that is India, where planners erroneously believe that limiting FAR will limit population density rather than simply reduce the size of living quarters, resulting in terrible overcrowding and living conditions for tens of millions of Indian citizens. Stephen Smith at Market Urbanism has even called the relaxation of this FAR limit the most needed urbanist reform in the world. And it is hard to disagree when one sees the results.

Conclusion

So, the Floor-Area Ratio, it's a great way to measure building density, however, it isn't a very good vector for planning and regulations, unless one starts an approach like the one I described for incremental city building. It is important to understand that developers and consumers have a tendency to act in a way planners don't expect to maximize their own benefits regardless of the goals of regulations set in place. It is thus important to understand the possible effects that various ways of controlling the built area may have, and to do that, we have to understand what economic actors want and how they think, for they show great innovation in skirting around regulations.