Now that I'm past financial myths, let's get on to myths held against other road users, whether they be on foot, on bikes or in transit

Myth 1: I respect stop signs, cyclists should have to do it too and make a full stop at them

This absolutely needs to be the first one.

First of all, I've driven 30 000 km a year for 6 years (20 000 miles) on a manual car, so let me point out the elephant in the room: most car drivers do not make full stops at stop signs if they don't absolutely need to. Most car drivers slow down to 5-10 km/h (3-6 mph), look left and right, then start accelerating again. To car drivers, they feel like they have stopped compared to their previous speed, but to pedestrians and cyclists, it's evident the cars aren't really fully stopped. As a stickshift driver, this reality was quite evident to me, starting from a stop on a manual car is quite more difficult than starting from a slow roll, so I realized that most of the time, I didn't fully stop, only when I needed to. I never got a ticket, and probably slowed down more than most at stop signs (as I could see when on 2-lane streets besides someone else).

So the first part is wrong. Any car driver who tells you he respects stops signs all the time and makes a full stop is probably... let's say, "exaggerating" his obedience to the law.

As to cyclists, asking them to do a full stop is really going too far. Unlike cars, cyclists' kinetic energy comes from their muscles, it's not just a matter of moving one foot from the brake to the gas pedal, they need to provide the energy to get moving, and it's the hardest part of cycling. Think about fuel consumption in non-hybrid cars, what happens in stop-and-go traffic? Fuel consumption skyrockets, because you need to convert energy from the gas in your tank to kinetic energy, then you waste that energy in the form of heat every time you brake, so you need to replenish it by burning more gas to get moving again.

Asking for cyclists to make a complete stop and putting their foot on the ground is like asking for car drivers to put their cars in park or in neutral and shut off the engine at every stop.

I'm going to do the rest of the arguments against full stops as bullet points to keep it shorter:

So cyclists shouldn't be asked to do complete stops. It is not safer, it is less safe.

First of all, I've driven 30 000 km a year for 6 years (20 000 miles) on a manual car, so let me point out the elephant in the room: most car drivers do not make full stops at stop signs if they don't absolutely need to. Most car drivers slow down to 5-10 km/h (3-6 mph), look left and right, then start accelerating again. To car drivers, they feel like they have stopped compared to their previous speed, but to pedestrians and cyclists, it's evident the cars aren't really fully stopped. As a stickshift driver, this reality was quite evident to me, starting from a stop on a manual car is quite more difficult than starting from a slow roll, so I realized that most of the time, I didn't fully stop, only when I needed to. I never got a ticket, and probably slowed down more than most at stop signs (as I could see when on 2-lane streets besides someone else).

So the first part is wrong. Any car driver who tells you he respects stops signs all the time and makes a full stop is probably... let's say, "exaggerating" his obedience to the law.

As to cyclists, asking them to do a full stop is really going too far. Unlike cars, cyclists' kinetic energy comes from their muscles, it's not just a matter of moving one foot from the brake to the gas pedal, they need to provide the energy to get moving, and it's the hardest part of cycling. Think about fuel consumption in non-hybrid cars, what happens in stop-and-go traffic? Fuel consumption skyrockets, because you need to convert energy from the gas in your tank to kinetic energy, then you waste that energy in the form of heat every time you brake, so you need to replenish it by burning more gas to get moving again.

Asking for cyclists to make a complete stop and putting their foot on the ground is like asking for car drivers to put their cars in park or in neutral and shut off the engine at every stop.

I'm going to do the rest of the arguments against full stops as bullet points to keep it shorter:

- Cyclists already go at a much slower speed than cars, 15-20 km/h, slightly slowing down would bring them to the same speed most cars make their "stops" at.

- Cyclists have a better field of view than car drivers as they have no windshield and pillar obstructions to their sight.

- Cyclists feel more vulnerable so are in general more careful as they know that if there is a collision with a car, they will suffer much more.

- Cyclists starting from a full stop are unstable and very slow, bikes become stable only at speed, so if they have to make a full stop, they will take more time to cross the intersection and be less stable while doing so, which increases the chances of an impatient car driver cutting them.

- Cyclists with speed are able to maneuver better, so if there is a situation that requires a reaction on their part, they are better off maneuvering when they have some speed.

- If cyclists are forced to stop at every stop sign, it turns them off of residential streets and back roads that are full of them and incites them to try their luck on main arterials where there are no stops, and which are much more dangerous for them as traffic is more important and faster.

So cyclists shouldn't be asked to do complete stops. It is not safer, it is less safe.

Myth 2: Pedestrians/cyclists should have to pay insurance too, just like car drivers!

Why do we pay insurance on cars? Well, first there is a protection against natural damages (ex: hail), thefts and vandalism, but these are all for when the car is parked, just protection for your property. The main part of car insurance is not actually about protecting YOUR car, but protecting YOU from civil lawsuits for the damages for which YOU are responsible to your car, other cars on the road and people. Basically, the main part of car insurance is civil liability, to pay the people that you hurt, not to protect your own car from others. In fact, in many places this is the ONLY mandatory part of your car insurance. You don't need to be protected against theft, or against natural damages, you only need civil liability protection.

So why is that? Because as a car driver, the potential damage you can cause to others is tremendous. Even small fender-benders can cause thousands of dollars in damages. Cars are frequently driven at speed at which if they hit a pedestrian or a cyclist, they WILL kill them. And indeed, car accidents cause a lot of damages, how much is a matter of debate. In the US, the CDC claimed that motor vehicle crashes cost the country 99 billion dollars in damages, the motorist lobby AAA claimed car crashes cost society 300 billion dollars and the NHTSA claims 871 billion dollars in costs. Why such huge discrepancy? Well, what is a life worth? In 2012, nearly 34 000 people died in car crashes in the United States.

A car hits a wall at 50 km/h (30 mph), how much damage does it cause? A car hits another car at 50 km/h, how much damage does it cause? A car hits a pedestrian or a cyclist at 50 km/h, how much damage does it cause? In order: lots, lots (and maybe death), not much material damage but the pedestrian or cyclist ends up in the ER or the morgue.

Now, a pedestrian walks into a wall at 5 km/h (3 mph), how much damage does the squishy human cause to the wall? Basically, none. What if a cyclist runs into a parked car? Actually, when I was younger, one of my brothers once ran into a few parked cars on his bike in one month period, we laughed at him... and we could laugh, because he only scraped his knee and didn't so much as scratch the paint on the cars, no lasting damage done.

Okay, there is the freak accident where someone on a bike hits an old person who expires from the impact, but that is extremely, extremely rare.

The point is, pedestrians and cyclists cannot cause much damage when traveling, they have not enough mass nor speed to do much damage. So even if you got them to buy insurance, that insurance would be negligible, to the tune of a nickel a day or the like. Sure, pedestrians and cyclists are likely in a car crash, but that's because they are killed, they do not kill. Cars kill pedestrians and cyclists, not the other way around.

The real reason many ask for insurances on cyclists is to discourage people from riding bikes by putting red tape in their way, not because they really need insurance. In many cases, people have other insurances that covers them while walking or biking.

Myth 3: reforms to help pedestrians and cyclists come at my expense!

In reality, many reforms to help pedestrians and cyclists, like building better sidewalks or bike lanes, come at no cost for car drivers. Their lanes are simply narrowed a bit, which is a good thing as it incites drivers to go at a speed that is more appropriate for the place they're driving in.

But that's not the main point that says this myth is wrong. The truth is that reforms to help pedestrians and cyclists help everyone because everyone is a pedestrian at some point, and most people can be cyclists. Some car drivers act as if the idea of leaving their car at home or even on a parking lot and doing the rest on foot was like asking people to leave their legs at the door. But every human being is a pedestrian (even those in wheelchairs count as pedestrians), so anything to help pedestrians be more comfortable and welcome in a place helps all human beings. Being pedestrian-friendly means being human-friendly.

Driving a car is something that one does, not something that one is. It is sad to see people define their identity as car drivers as if it was indistinguishable from their core identity as an human being.

Myth 4: these bus only lanes are only reducing capacity and creating congestion, they're mostly empty!

First of all, it's important to note that even the simple bus can carry as many as 50 or 60 people, depending on how seats are arranged and how much proximity people will tolerate. So when there is congestion, it's likely the peak hour, so every bus is likely to be nearly full, or carrying at least 20-30 people, especially on roads where there are congestion.

As cars have about 1,25 person in them, that means that the equivalent of a car saturation flow of one car per 2 seconds for a bus lane is one bus every minute or so.

Visually, both lanes in the image below carry about the same amount of people:

As cars have about 1,25 person in them, that means that the equivalent of a car saturation flow of one car per 2 seconds for a bus lane is one bus every minute or so.

Visually, both lanes in the image below carry about the same amount of people:

| I know it's hard to see, click on it to see it a bit larger, cars in the top lane in blue, buses in the bottom lane in green, yes, it is to scale |

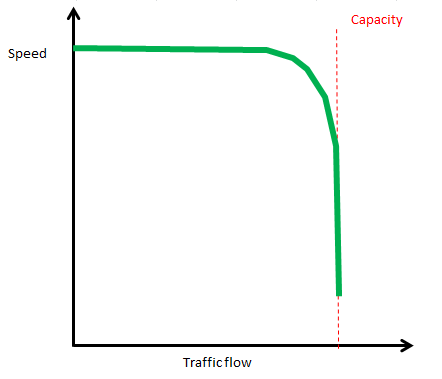

Bus lanes in street grids are a different animal. Street grids tend to have a lot of capacity and to never be really jammed. When they are, it's a disaster. However, as streets cross each other frequently, speed falls progressively as traffic increases. If I was to model speed and traffic vs capacity for highways and streets, I'd draw something like this:

|

| Speed vs traffic flow for an highway, speed only falls near capacity |

|

| Speed vs traffic flow for streets in a grid, speed falls progressively as flows increase |

So, each lane in a street had a slower free flow speed and lower capacity than an highway lane, and speed falls progressively as traffic increases rather than maintaining itself then dropping like a stone. That's because of traffic lights and stops mostly. However, as there are a lot more lanes in a street grid than on highways, street grids have better capacity overall than highway systems.

So in the case of urban streets, bus lanes are justified even without congestion to speed up buses by reducing the congestion of the bus lane by cars. In general, bus lanes can slow down cars a bit, but the combined effect of making buses more attractive and the great number of parallel streets means that car traffic is not that affected by urban bus lanes.

Myth 5: most accidents involving pedestrians and cyclists are their own fault

The reality is that pedestrians and cyclists are painfully aware of how vulnerable they are when on the road and generally take great care not to be in the path of vehicles. However, often the roads and streets have not been built with them in mind, with huge detours demanded just to cross the street when intersections are few, like we tend to do in order to speed up cars. When pedestrians and cyclists break the law, it is often because respecting the law is either extremely time-consuming for them (walking or biking 5-10 minutes more just to get a legal crossing) or is even more dangerous than no respecting it (for instance, jaywalking midblock may be safer than crossing at an intersection near capacity where impatient drivers will cut pedestrians off while turning left and right to be able to get through on the green light).

Car drivers are no better on that account, how many of them, when they see a yellow light, press down on the gas rather than the brake in order to beat the light?

Ultimately, as car drivers are driving vehicles that are much bigger, heavier and faster, they bear the most responsibility for what happens on the road. When a collision is eminent, pedestrians and cyclists are extremely limited in what they may do, a pedestrian may only deviate from their position by 1 or 2 meters, a cyclist, not by much more. A car can deviate by a lot longer distances thanks to their speed, brakes and steering.

The fact of the matter is also that the tests of shared spaces, spaces shared by pedestrians, cyclists and car drivers without predetermined right of way, have been proven to be extremely safe. Looking at videos of how they operate, we can notice that pedestrians and cyclists are actually not that predictable, except in that once they set their direction, they don't deviate from it as the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Shared spaces are effective because car drivers are forced to be more careful, to slow down and to prepare for unexpected movements of pedestrians and cyclists.

Car drivers have the highest responsibility for traffic safety, placing the blame on pedestrians and cyclists is dangerous because it doesn't work. Only a realization by car drivers that they need to be more careful and give priority seems to work to make roads safer.

Myth 6: density causes congestion

I know, it doesn't fit so well in this category of sharing the road, but it's the best place for it of all the categories. Still, in order to favor pedestrian, biking and transit trips, density is inevitably part of the solution, but many people oppose it because they think it will yield great congestion in residential areas.

The reality is that density doesn't cause congestion at all, well, at least not residential density. I already pointed out in another article studying mode shares in different neighborhoods in Montréal and Québec that car mode share is strongly affected by increasing density, in an almost linear relationship. As density increases, other modes of transport become more viable, so people are less likely to take cars to go anywhere.

One important point to remember is that if people cannot live in existing areas closer to downtown, they do not disappear. Housing supply doesn't create demand, if people can't live in dense, multi-modal areas, then they will live in car-dependent suburbs. And when they live in car-dependent suburbs, guess what they will use to get around? And where will they go with their cars?

So, if anything, refusing density and pushing people farther out is what is most likely to create more traffic and more congestion. And indeed, though congestions occur in cities, or at least at entry points to cities, those who create that congestion are not the city residents, but the suburban residents. You could empty all the city neighborhoods of residents and there would be just as much congestion, in fact, that's what many American cities did like Detroit, and they still end up with congestion.

There is another reason why congestion is the consequence of sprawl: as people settle farther from the city and its jobs and services, they need to travel longer distances to reach these, in order to maintain adequate commuting times, they require high-speed roads, 70 km/h and above (45+ mph). But these roads are generally not all that frequent because they require more space and at least limited intersections. So as they converge on these few high-speed roads, they jam them and create congestions at chokepoints. In a dense city with a low-speed street grid, traffic can distribute itself more evenly and avoid the stop-and-go gigantic lines of cars.

No comments:

Post a Comment