For those who do not know, Donald Shoup is an American expert of parking policy. He is also the author of the very important "The high cost of free parking", the foremost criticism of American parking policy practices, detailing the irrationality of off-street parking requirements and their negative impacts on American cities. Note: I have not read his book, but have been exposed to his ideas through other books (Suburban Nation, Walkable City) and in interviews of the man.

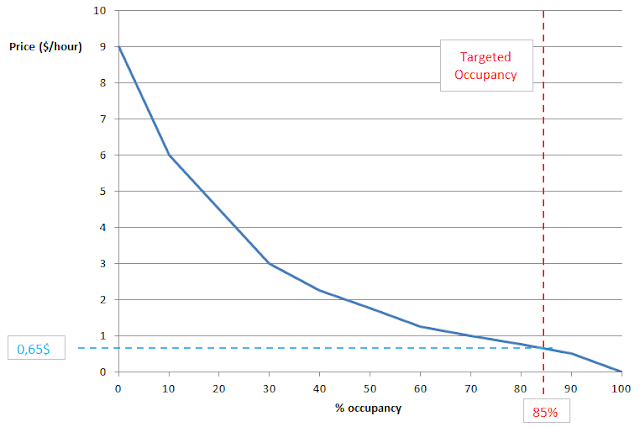

One of his most famous recommendations is to implement a policy targeting a 85% occupancy rate for street parking by modulating parking prices. That is, by understanding parking demand as a price-responsive quantity, when parking is overloaded, prices can simply be increased to return to a desired occupancy rate by depressing demand. Why 85%? Because it's a good compromise between optimal use of the parking spots and allowing for drivers to find a parking spot easily, avoiding cars driving around for 5-10 minutes to find a parking spot. It also assists in turnover, allowing more people to park by limiting in time the duration each car remains parked.

In a way, that's a bit like my Easy Solution to Congestion a few posts back:

One of his most famous recommendations is to implement a policy targeting a 85% occupancy rate for street parking by modulating parking prices. That is, by understanding parking demand as a price-responsive quantity, when parking is overloaded, prices can simply be increased to return to a desired occupancy rate by depressing demand. Why 85%? Because it's a good compromise between optimal use of the parking spots and allowing for drivers to find a parking spot easily, avoiding cars driving around for 5-10 minutes to find a parking spot. It also assists in turnover, allowing more people to park by limiting in time the duration each car remains parked.

In a way, that's a bit like my Easy Solution to Congestion a few posts back:

|

| The Easy Solution to Congestion |

Anyway, this approach of targeting a certain occupancy rate by modulating price is what I call the Shoupian approach.

Donald Shoup has promoted the use of automatic parking meters that could adjust prices in real time based on current occupancy.

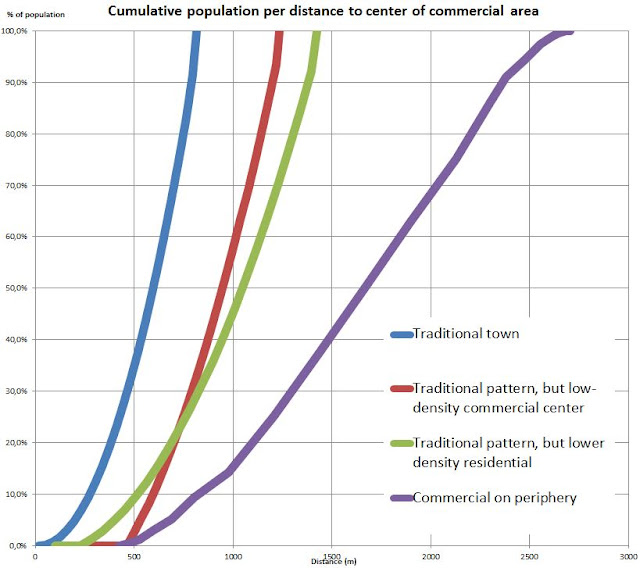

This approach was tailor-made for a particular situation common to North America where cities are trying to maintain their old main streets alive. These are areas built largely before parking minimums, with a lot of commercial uses. There may be a few parking lots, but for the most part, parking demand is satisfied through on-street parking.

So I've been thinking about that proposal a bit, and I'd like to bring up a few things about it, because I do not think it's the best approach ever. It may be the best approach that is likely to be put in place, but there are a few things that annoy me a bit with it.

But first, let me address something that is often erroneously claimed about it:

|

| A parking demand curve and the Shoupian Approach, the price that yields a 85% occupancy rate at that point in time is 0,65$ per hour |

This approach was tailor-made for a particular situation common to North America where cities are trying to maintain their old main streets alive. These are areas built largely before parking minimums, with a lot of commercial uses. There may be a few parking lots, but for the most part, parking demand is satisfied through on-street parking.

So I've been thinking about that proposal a bit, and I'd like to bring up a few things about it, because I do not think it's the best approach ever. It may be the best approach that is likely to be put in place, but there are a few things that annoy me a bit with it.

But first, let me address something that is often erroneously claimed about it:

The Shoupian approach is not a market approach

Many people call the Shoupian approach a "market-based" approach because prices vary with demand. That is however not correct. In the Shoupian approach, the parking authority is still publicly-owned and parking is still a public service. So it's a monopoly situation with one parking provider.

What defines a market is a great number of providers competing to provide a particular good and their profit motive. Their goal is to provide goods to satisfy demand at a price over the cost of production so that a profit can be obtained. These providers have one goal: maximize profits.

So in a market, there is a companion to the demand curve, the supply curve. What the supply curve means is that when prices go higher, it entices new providers to enter the market and produce that particular good, thus increasing the quantity of it on the market. For example, if you're sitting on an oil well from which you can produce oil at 70$ a barrel, but oil is currently at 60$ a barrel on the world markets, you're going to keep sitting on it, why produce oil if you're just going to lose money on each barrel you produce (supposing you have no fixed cost)? If oil on the market increases to 80$ a barrel, THEN you will start producing as many barrels as you can sell.

This creates a feedback system wherein higher prices for a good gets people to produce more of it, thus increasing supply and stabilizing the price (keeping it from rising).

The Shoupian approach has no such feedback system, it supposes that parking supply is fixed, then determines a price to maintain a desired demand for it. In effect, the Shoupian approach is a rationing system, using price as a means of rationing.

The lack of profit motive also has a major impact. Shoup admits that in most places, his approach actually results in free parking or in lower fees than are currently in place where parking is already metered. The price is chosen only for its ability to reach the desired 85% occupancy rate, so if the occupancy rate is below 85% even when parking is free, then parking should be free.

A for-profit parking operator on the other hand doesn't target occupancy, he targets profit.

For example, let's take this demand curve for parking at a point in time:

The Shoupian approach says the price of parking should be such that occupancy is 85%. Well, in this case, that price is 0$. So parking should be free.

Now, let's put ourselves in the shoes of a for-profit parking operator. He wants to profit from his parking, that's all. So what he's going to do is simply multiply the occupancy rate by the price, then subtract the cost of enforcement of the parking charge (for example, an employee paid 15$/hour per 40 spots, making sure people pay their fare and calling the cops if they won't).

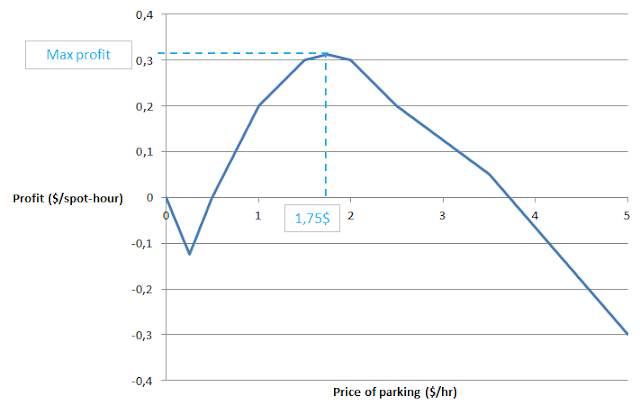

In the end, he can get a new graph that looks like this:

So in this case, the for-profit operator would prefer a price of 1,75$/hour to maximize his profits.

To sum up, the Shoupian parking operator starts from a desired occupancy rate, then fixes price according to it. The for-profit operator determines the prices that would yield the most profit and fixes it, and the actual occupancy rate is irrelevant to him (but if the occupancy rate is always low, he may look to unload some of his parking spots that don't earn him enough money, another effect of market feedbacks).

So a for-profit parking system would generally result in much higher fees than a Shoupian approach, except in periods of very high demand. The Shoupian approach sees no problem with free parking, as long as demand remains low, because it sees parked cars as a good in itself. The more parked cars, the better, because that means more people coming into the area (for example: coming shopping).

Note that if a for-profit owner owns both a building and its parking, he may also accept free parking because enticing more people to come park at the building is good for him as he gets profits from the building itself, so he may take a loss on his parking to get higher profits from the building he owns.

Anyway, that leads to my first beef with the Shoupian approach...

The Shoupian approach just ignores completely the cost of providing the parking, it is completely irrelevant in its price-fixing reflexion. It even allows for free parking to exist. And even when there is a fee, Donald Shoup recommends the money NOT be used to pay for the maintenance of the parking spots, but to provide new amenities to the commercial area where the fees are collected (which makes it far more palatable for the community and thus helps social acceptance of the fees).

The reason why a socialist like me is interested in a market-based system is because a for-profit operator by definition has to apply "user-payer". He cannot provide a good for less than it costs him to produce, or he would go bankrupt. Therefore, a market for parking achieves the objective of making car drivers pay the full cost of the parking they use.

In a way, the Shoupian approach is like a congestion charge. It only applies to overloaded infrastructure, leaving under-used infrastructure free to use and subsidized by society. I criticized the congestion charge for this because it can lead to free highways in suburbs and expensive streets in cities, thus having the city subsidizing the suburbs. A Shoupian approach can have the same effect of leaving parking in low-density area free and subsidized while charging high prices for downtown parking. Parking in low-density areas are cheaper to provide, so it should be cheaper, but not subsidized, not free.

If off-street parking requirements are ill-advised and unscientific, what would we say of planners building a fixed amount of street parking without regard to the land use expected in an area? But anyway, that is just my typical rant on street parking, let's move on...

A market-based approach to parking on the other hand DOES provide a mechanism to determine the amount of parking to be built. You can probably estimate that if you build a parking spot in a given location where there was none, this spot will be occupied most of the time by a car (though depending on the land use around it, it may be free at night or during the day). But as you keep adding parking spots to a lot, each additional spot will be occupied less often than the previous one.

Think of a shopping mall's parking, the spots near the doors are nearly always in use during the business hours, the spots at the farthest spot from the door are always empty, except maybe once every year. Well, a parking spot only generates revenue when a car is in it, whether through hourly fees or by the revenue generated by a customer (in the case of a free parking attached to a store). So it would stand to reason that a parking spot occupied 30% of the time would generate twice as much revenue as one occupied just 15% of the time, yet both are likely to cost the same to build and maintain.

So again, an example, let's say someone builds a parking lot and estimates the marginal occupancy rate of parking spots this way:

Well if he gives a flat value of 2$ per hour of revenue each hour a parking spot in in use, and he estimates that each parking spot has an annualized cost of 800$ (including annualized cost of land and construction, plus yearly maintenance and operation), then he could get the following graph:

In that example, building more than 30 parking spots is wasteful because the revenue of each additional parking spot will be less than the annualized cost. So a smart developer will not build more than he can justify economically.

OK, you don't actually need a market to do so. You could have a public parking authority that is asked to self-fund and it would follow the same logic, competition or not. I'm not opposed to the idea as such, but a market may be simpler to put in place.

The Shoupian approach is fine with free, subsidized parking as long as occupancy rate is below 85% if prices are zero and it won't follow the market prices if these result in less than an 85% occupancy. This creates a weird interplay with private parking options as you have different market participants with completely different behavior, one targeting an occupancy ratio, the others maximizing revenue.

At times of great affluence, where every parking lot can be full, it can be workable, but in downtimes, the Shoupian operator will have no qualm about selling parking below cost to obtain its 85% occupancy ratio. This, in economic terms, is effectively dumping. Dumping is when a producer sells his product below cost in order to obtain a larger market share than his competitors, generally with the aim of pushing them to bankruptcy.

In this situation, though there is no ill intent, it remains that the Shoupian parking authority will end up dumping its parking on the market, because it can and will sell its parking below cost to achieve its occupancy goal, to the detriment of private parking options.

This dumping can reduce the revenues from private parking options and disrupt the creation of parking markets.

However, I'm not keen on the fact that it is also recommended to lower rates when occupancy is below 85%, even to make it free if need be. I understand the logic: people who come park there contribute to the local economy by shopping around, going to restaurants, etc... The policy seeks to maximize parking use to get more people to come... but personally, I don't want to maximize parking use, I would prefer for parking to be used less by having people come on foot, on a bike or on transit. I don't want to force them out of their cars, but I do want them to pay for parking on a "user-payer" basis to use price to signal how expensive cars are to accommodate in cities and to encourage other means of getting around. Free parking is one of the worst subsidies to car-driving, and the most significant one in urban areas, and it is one that the Shoupian approach can maintain as long as occupancy rates for free parking doesn't reach 85%. The underlying assumption seems to be that people who come to an area by car would never come to it through any other mode.

In my ideal world, there would be no street parking at all, all parking would be provided through a for-profit market or by store owners willingly building parking (without being required to). However, in a more practical way, I do agree with Shoup that, when parking on the street is very rare, hiking the fare to lower occupancy rates on street parking to 85% is a good idea, but I would prefer for parking rates to have a floor, so that it never goes below a certain cost, no matter how low the occupancy gets. In other words, keep the current hourly rates, but have surge prices for times with high demand.

Also, if there are private parking lots, I think it would be best to either include them in the surge prices or to have the parking authority actually match the market price of parking by copying the price private operators put on their parking.

What defines a market is a great number of providers competing to provide a particular good and their profit motive. Their goal is to provide goods to satisfy demand at a price over the cost of production so that a profit can be obtained. These providers have one goal: maximize profits.

So in a market, there is a companion to the demand curve, the supply curve. What the supply curve means is that when prices go higher, it entices new providers to enter the market and produce that particular good, thus increasing the quantity of it on the market. For example, if you're sitting on an oil well from which you can produce oil at 70$ a barrel, but oil is currently at 60$ a barrel on the world markets, you're going to keep sitting on it, why produce oil if you're just going to lose money on each barrel you produce (supposing you have no fixed cost)? If oil on the market increases to 80$ a barrel, THEN you will start producing as many barrels as you can sell.

This creates a feedback system wherein higher prices for a good gets people to produce more of it, thus increasing supply and stabilizing the price (keeping it from rising).

The Shoupian approach has no such feedback system, it supposes that parking supply is fixed, then determines a price to maintain a desired demand for it. In effect, the Shoupian approach is a rationing system, using price as a means of rationing.

The lack of profit motive also has a major impact. Shoup admits that in most places, his approach actually results in free parking or in lower fees than are currently in place where parking is already metered. The price is chosen only for its ability to reach the desired 85% occupancy rate, so if the occupancy rate is below 85% even when parking is free, then parking should be free.

A for-profit parking operator on the other hand doesn't target occupancy, he targets profit.

For example, let's take this demand curve for parking at a point in time:

|

| Example of a demand curve for parking (for a fixed supply of parking) |

Now, let's put ourselves in the shoes of a for-profit parking operator. He wants to profit from his parking, that's all. So what he's going to do is simply multiply the occupancy rate by the price, then subtract the cost of enforcement of the parking charge (for example, an employee paid 15$/hour per 40 spots, making sure people pay their fare and calling the cops if they won't).

In the end, he can get a new graph that looks like this:

|

| A profit graph relative to price set on the parking (note that since free parking doesn't necessitate enforcement, it doesn't lose money despite having no revenue) |

To sum up, the Shoupian parking operator starts from a desired occupancy rate, then fixes price according to it. The for-profit operator determines the prices that would yield the most profit and fixes it, and the actual occupancy rate is irrelevant to him (but if the occupancy rate is always low, he may look to unload some of his parking spots that don't earn him enough money, another effect of market feedbacks).

|

| The Shoupian and for-profit reasoning put on the graph of the demand curve |

Note that if a for-profit owner owns both a building and its parking, he may also accept free parking because enticing more people to come park at the building is good for him as he gets profits from the building itself, so he may take a loss on his parking to get higher profits from the building he owns.

Anyway, that leads to my first beef with the Shoupian approach...

The Shoupian approach is not a "user-payer" approach

"User-payer" means that the user of a particular good ought to pay a price at least equal to the cost of providing it. If something costs 2$ to provide, you should pay 2$ or more. When the "user-payer" principle isn't respected, it means that someone else is paying for that good, in effect, a subsidy. I'm not against a subsidy on principle (I do identify as a socialist), but subsidies encourage consumption of goods, so you need to be able to argue that encouraging that consumption satisfies social or moral objectives (for example: health care subsidies). In my view, encouraging the consumption of parking is not a good idea.The Shoupian approach just ignores completely the cost of providing the parking, it is completely irrelevant in its price-fixing reflexion. It even allows for free parking to exist. And even when there is a fee, Donald Shoup recommends the money NOT be used to pay for the maintenance of the parking spots, but to provide new amenities to the commercial area where the fees are collected (which makes it far more palatable for the community and thus helps social acceptance of the fees).

The reason why a socialist like me is interested in a market-based system is because a for-profit operator by definition has to apply "user-payer". He cannot provide a good for less than it costs him to produce, or he would go bankrupt. Therefore, a market for parking achieves the objective of making car drivers pay the full cost of the parking they use.

In a way, the Shoupian approach is like a congestion charge. It only applies to overloaded infrastructure, leaving under-used infrastructure free to use and subsidized by society. I criticized the congestion charge for this because it can lead to free highways in suburbs and expensive streets in cities, thus having the city subsidizing the suburbs. A Shoupian approach can have the same effect of leaving parking in low-density area free and subsidized while charging high prices for downtown parking. Parking in low-density areas are cheaper to provide, so it should be cheaper, but not subsidized, not free.

The Shoupian approach doesn't help determine the quantity of parking

As I said, the Shoupian approach of targeting occupancy is essentially a rationing system. But a rationing system is generally used in a case of fixed supply. There is no mechanism to vary parking supply in reaction to price signals. Street parking is, in the end, a very dumb thing, even dumber than minimum parking requirements. Whether you are in suburbs or in the heart of a dense city, it provides roughly the same amount of parking per square kilometer (I estimated up to 5 000 spots per square kilometer, 13 000 per square mile). Some people pretend that this is essentially "free" space anyway, as if roads are going to be built wide enough to have cars parked on it anyway, but that's just not true. You can build narrower roads, for some density gains, or build bike paths or larger sidewalks with that space.If off-street parking requirements are ill-advised and unscientific, what would we say of planners building a fixed amount of street parking without regard to the land use expected in an area? But anyway, that is just my typical rant on street parking, let's move on...

A market-based approach to parking on the other hand DOES provide a mechanism to determine the amount of parking to be built. You can probably estimate that if you build a parking spot in a given location where there was none, this spot will be occupied most of the time by a car (though depending on the land use around it, it may be free at night or during the day). But as you keep adding parking spots to a lot, each additional spot will be occupied less often than the previous one.

Think of a shopping mall's parking, the spots near the doors are nearly always in use during the business hours, the spots at the farthest spot from the door are always empty, except maybe once every year. Well, a parking spot only generates revenue when a car is in it, whether through hourly fees or by the revenue generated by a customer (in the case of a free parking attached to a store). So it would stand to reason that a parking spot occupied 30% of the time would generate twice as much revenue as one occupied just 15% of the time, yet both are likely to cost the same to build and maintain.

So again, an example, let's say someone builds a parking lot and estimates the marginal occupancy rate of parking spots this way:

|

| Example of a marginal occupancy graph for the number of spots in a parking |

|

| Marginal revenue vs annualized cost |

OK, you don't actually need a market to do so. You could have a public parking authority that is asked to self-fund and it would follow the same logic, competition or not. I'm not opposed to the idea as such, but a market may be simpler to put in place.

The risk of "dumping" and disrupting the emergence of a parking market

So could the solution simply be to have on-street parking (and any potential publicly-owned parking lot) follow the Shoupian approach and let private developers develop a parallel parking market? Well, there is a big issue when doing that, because the two are in competition, yet do not share the same logic.The Shoupian approach is fine with free, subsidized parking as long as occupancy rate is below 85% if prices are zero and it won't follow the market prices if these result in less than an 85% occupancy. This creates a weird interplay with private parking options as you have different market participants with completely different behavior, one targeting an occupancy ratio, the others maximizing revenue.

At times of great affluence, where every parking lot can be full, it can be workable, but in downtimes, the Shoupian operator will have no qualm about selling parking below cost to obtain its 85% occupancy ratio. This, in economic terms, is effectively dumping. Dumping is when a producer sells his product below cost in order to obtain a larger market share than his competitors, generally with the aim of pushing them to bankruptcy.

In this situation, though there is no ill intent, it remains that the Shoupian parking authority will end up dumping its parking on the market, because it can and will sell its parking below cost to achieve its occupancy goal, to the detriment of private parking options.

This dumping can reduce the revenues from private parking options and disrupt the creation of parking markets.

Conclusion

I get it, the Shoupian approach is made for a certain political and urban context in America. It is made to deal with areas where most parking is already provided by the city through street parking. It is a much better alternative to dealing with parking issues than parking requirements for developers. Basically, reduce demand at hours of great demand through rate hikes rather than increasing parking supply and keeping it free. I really do get it. And the idea of increasing fares when occupancy is above 85% makes sense.However, I'm not keen on the fact that it is also recommended to lower rates when occupancy is below 85%, even to make it free if need be. I understand the logic: people who come park there contribute to the local economy by shopping around, going to restaurants, etc... The policy seeks to maximize parking use to get more people to come... but personally, I don't want to maximize parking use, I would prefer for parking to be used less by having people come on foot, on a bike or on transit. I don't want to force them out of their cars, but I do want them to pay for parking on a "user-payer" basis to use price to signal how expensive cars are to accommodate in cities and to encourage other means of getting around. Free parking is one of the worst subsidies to car-driving, and the most significant one in urban areas, and it is one that the Shoupian approach can maintain as long as occupancy rates for free parking doesn't reach 85%. The underlying assumption seems to be that people who come to an area by car would never come to it through any other mode.

In my ideal world, there would be no street parking at all, all parking would be provided through a for-profit market or by store owners willingly building parking (without being required to). However, in a more practical way, I do agree with Shoup that, when parking on the street is very rare, hiking the fare to lower occupancy rates on street parking to 85% is a good idea, but I would prefer for parking rates to have a floor, so that it never goes below a certain cost, no matter how low the occupancy gets. In other words, keep the current hourly rates, but have surge prices for times with high demand.

Also, if there are private parking lots, I think it would be best to either include them in the surge prices or to have the parking authority actually match the market price of parking by copying the price private operators put on their parking.