I speak a lot about Japan on this blog, so I might as well explain where I'm coming from. The intro gives personal background, if you're not interested (I don't blame you), skip to the "End of Background Info" line.

I was raised in the suburb of Boucherville, in a particularly car-dependent area of it (there are walkable areas in the suburb, I was just not in one). Nonetheless, I was never a car lover growing up, I waited a long time to get my driver's license, I was maybe 19 or 20 when I finally decided to get it. Though my area had no retail or services in proximity, it had decent transit service to get to the subway of Montréal and I used transit to get to CÉGEP and university after high school, only driving regularly after getting a job.

Though I didn't think of urbanism much growing up, I recognize that my appreciation for walkable areas is an old one in me. When I was young, I visited the old areas of Québec City and fell in love with it. I told my parents "I can go there and spend days just walking the city and be content that it was time well spent".

Of course, now I know that Québec City is an old, dense European core surrounded by endless North American sprawl. So it is a city full of charm, as long as you keep to the old city and neighboring areas only.

Still, I never really connected this to urbanism much. I even had a phase where I appreciated a lot cars as everyday transport tools and examined the merits of cars a lot, concentrating on fuel economy and efficiency in small cars rather than sports cars. I bought my first car in 2008, the year after I started working, a manual 2.4L Saturn ION 2007 leftover from the previous year. Got a hell of a deal on it too, worth learning to drive stick for it. For 5 years, I did 110 km a day of commuting by car (around 70 miles), 45 minutes each way. Spending my days at work behind a computer and driving everywhere, I gained a lot of weight. Commuting apart, going on a drive was a pleasure of mine, I especially loved driving on forest roads after dark. I didn't speed, I just liked the sensation of driving with the headlights on in the middle of a wild forest on a sinuous road, illuminated by the dashboard lights.

In 2009, a significant event happened which shaped my attitude to transport and awakened me to urbanism. I went to Japan. I had always been interested in and loved Japanese culture, and I admit to being somewhat of an otaku. What I hadn't expected when I went to Japan was falling in love with Japanese cities and its transport system. I was already taking pictures of normal streets and urban areas that most people ignored on my first trip.

I came back to Québec and I told my friends and family: "I left North America seeing cars as freedom... I came back and I looked upon my car as a weight I had to drag around". This tool of "liberty" had become a tool of "oppression" in my mind. Why did I need to get around in a cage of steel and glass that separated me from the world? I realized my world was one of bubbles: my home, my car, my cubicle, and I went from bubble to bubble all day long.

-END OF BACKGROUND INFO-

OK, so where am I going with this? Well, as I said, my conception of freedom of mobility shifted after a trip in Japan. So why did I feel so free in Japan, much freer than I feel in North America? Hint: look at the title.

Japanese cities tend to be very walkable, which is awesome, thanks to lax zoning which allows developments to follow an economic logic favoring the efficiency of density and proximity and a government that doesn't see as its primary purpose to provide free high-speed roads everywhere. But all this walkability and density would be wasted if people had no way to travel from one area to the other without cars.

That is why I'm not so keen on the "build worthwhile places first... then, maybe, transit" that some New Urbanists are doing. Yes, New Urbanist subdivisions are much better than traditional suburban ones, but in the end, in my mind, they are golden cages. Fine, they are walkable and have nice places, but whenever people want or have to go elsewhere or people from other areas want to visit, they need to take cars. Ultimately, the ability of people to get around is still conditional to the ownership of a motor vehicle.

Even in cities with good transit in North America, the restrictions to mobility are still much felt, because as soon as you leave a certain area, transit service just... stops. You sometimes have coach buses or Amtrak/VIA Rail going to other cities, but all the area between cities is often "off-limits" or extremely hard to reach.

In North America, regional travel is dependent on highways, high-speed roads built by State and provincial governments to allow people to go anywhere. But transit along highways is notoriously bad, highways are built for cars first and foremost (the French word is telling there: "autoroute", literally "automobile road").

In Japan, it is very different. Regional travel depends on an extraordinarily extensive rail system that dominates inter-city travel between 300 and 700 km (200 to 450 miles).

When we talk of trains in Japan, what most people think of is the Shinkansen, the famous "bullet train".

However, shinkansen lines aren't that common, most cities aren't directly connected to it. The real unsung hero of the Japanese transit system is the humble regional rail system which is extraordinarily extensive, and is the reason why when demanding directions on Google Maps for Japan, Google Maps defaults to transit.

The rail system is essentially as developed as regional highways in North America. Most areas worth going to are connected to rail lines, which is likely due to the fact that cities without rail access see their growth stunted. As a result, there is a feeling once in Japan that you only need to get to a train station, and the rest of the country becomes accessible to you. It may take a while, be expensive and require connections, but finding your way is easy and you know every stop will be well-organized. These trains are why I felt so free in Japan, almost no area is off-limits to people without cars thanks to these rail lines. At least, no area with any significant population. And the stations themselves are located right next to where you want to go most of the time: you get off the train into a pedestrian's paradise, even in small towns, rather than in the middle of nowhere.

Here are some attributes of the Japanese train system which makes it so awesome and which help define freedom of mobility differently.

Of course, we're talking of the train stations here. Train stations are generally located inside cities themselves, near the downtown area where most jobs and services are located, and at points of high population density. This is largely because developments flow to the train station naturally. In fact, as I mentioned in my last post, in real estate listings in Japan, the closest train station is one of the essential pieces of information provided.

So trains offer downtown-to-downtown travel, most destinations are likely located within walking distance of train stations, and bus services tend to originate from train stations, extending even more accessibility.

Of course, now I know that Québec City is an old, dense European core surrounded by endless North American sprawl. So it is a city full of charm, as long as you keep to the old city and neighboring areas only.

Still, I never really connected this to urbanism much. I even had a phase where I appreciated a lot cars as everyday transport tools and examined the merits of cars a lot, concentrating on fuel economy and efficiency in small cars rather than sports cars. I bought my first car in 2008, the year after I started working, a manual 2.4L Saturn ION 2007 leftover from the previous year. Got a hell of a deal on it too, worth learning to drive stick for it. For 5 years, I did 110 km a day of commuting by car (around 70 miles), 45 minutes each way. Spending my days at work behind a computer and driving everywhere, I gained a lot of weight. Commuting apart, going on a drive was a pleasure of mine, I especially loved driving on forest roads after dark. I didn't speed, I just liked the sensation of driving with the headlights on in the middle of a wild forest on a sinuous road, illuminated by the dashboard lights.

In 2009, a significant event happened which shaped my attitude to transport and awakened me to urbanism. I went to Japan. I had always been interested in and loved Japanese culture, and I admit to being somewhat of an otaku. What I hadn't expected when I went to Japan was falling in love with Japanese cities and its transport system. I was already taking pictures of normal streets and urban areas that most people ignored on my first trip.

|

| 5 years later, this photo still cracks me up |

-END OF BACKGROUND INFO-

OK, so where am I going with this? Well, as I said, my conception of freedom of mobility shifted after a trip in Japan. So why did I feel so free in Japan, much freer than I feel in North America? Hint: look at the title.

Japanese cities tend to be very walkable, which is awesome, thanks to lax zoning which allows developments to follow an economic logic favoring the efficiency of density and proximity and a government that doesn't see as its primary purpose to provide free high-speed roads everywhere. But all this walkability and density would be wasted if people had no way to travel from one area to the other without cars.

That is why I'm not so keen on the "build worthwhile places first... then, maybe, transit" that some New Urbanists are doing. Yes, New Urbanist subdivisions are much better than traditional suburban ones, but in the end, in my mind, they are golden cages. Fine, they are walkable and have nice places, but whenever people want or have to go elsewhere or people from other areas want to visit, they need to take cars. Ultimately, the ability of people to get around is still conditional to the ownership of a motor vehicle.

Even in cities with good transit in North America, the restrictions to mobility are still much felt, because as soon as you leave a certain area, transit service just... stops. You sometimes have coach buses or Amtrak/VIA Rail going to other cities, but all the area between cities is often "off-limits" or extremely hard to reach.

In North America, regional travel is dependent on highways, high-speed roads built by State and provincial governments to allow people to go anywhere. But transit along highways is notoriously bad, highways are built for cars first and foremost (the French word is telling there: "autoroute", literally "automobile road").

In Japan, it is very different. Regional travel depends on an extraordinarily extensive rail system that dominates inter-city travel between 300 and 700 km (200 to 450 miles).

|

| Source |

However, shinkansen lines aren't that common, most cities aren't directly connected to it. The real unsung hero of the Japanese transit system is the humble regional rail system which is extraordinarily extensive, and is the reason why when demanding directions on Google Maps for Japan, Google Maps defaults to transit.

|

| Part of a map of rail lines in Japan |

|

| Interior of a train on a private line to Nikko |

|

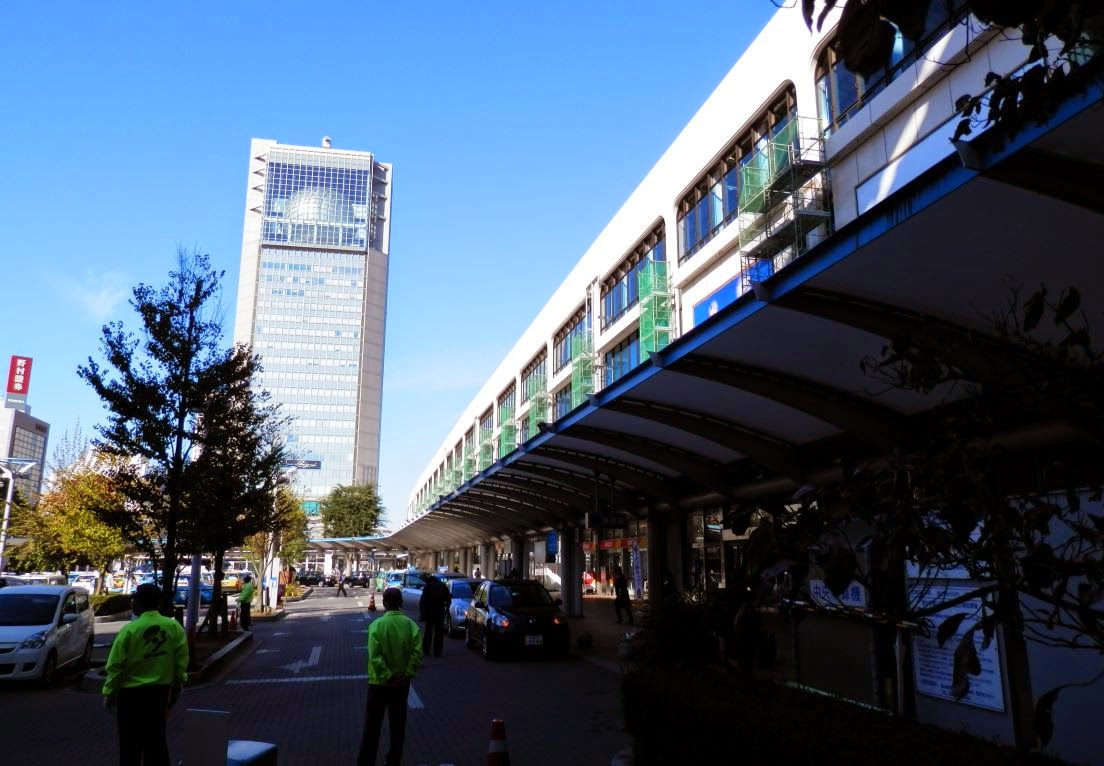

| Regional train station with train waiting |

The rail system is essentially as developed as regional highways in North America. Most areas worth going to are connected to rail lines, which is likely due to the fact that cities without rail access see their growth stunted. As a result, there is a feeling once in Japan that you only need to get to a train station, and the rest of the country becomes accessible to you. It may take a while, be expensive and require connections, but finding your way is easy and you know every stop will be well-organized. These trains are why I felt so free in Japan, almost no area is off-limits to people without cars thanks to these rail lines. At least, no area with any significant population. And the stations themselves are located right next to where you want to go most of the time: you get off the train into a pedestrian's paradise, even in small towns, rather than in the middle of nowhere.

Here are some attributes of the Japanese train system which makes it so awesome and which help define freedom of mobility differently.

1- The access points of the system are evident and well-located

Of course, we're talking of the train stations here. Train stations are generally located inside cities themselves, near the downtown area where most jobs and services are located, and at points of high population density. This is largely because developments flow to the train station naturally. In fact, as I mentioned in my last post, in real estate listings in Japan, the closest train station is one of the essential pieces of information provided.

|

| Example of apartment listing on Suumo.jp, with information about nearest train stations front and center, this apartment is in Furano, a town of about 25 000 people, far from any big city |

| ||

|

| Plaza in front of Nikko train station |

|

| Aizu Wakamatsu station |

2- Taking the train is as easy as taking the subway or a municipal bus

In North America, there is this obsession to differentiate long-distance trips from commuting trips as if the two needed absolutely to be treated differently. It's fine to wait on the platform for a subway or a commuter rail line, but for long-distance lines, it's not. People need to line up at the station and have tickets checked by employees before being allowed to go on the platform where the train is waiting for them. Pure lunacy. Because, yeah, if we want good consumer service, I'm sure airlines are the ones to copy, right?

In Japan, not only can people wait on the platform for any train, even the Shinkansen, but in most cases, there is no reservation needed. You don't need to reserve a seat or buy tickets a long time before. You show up, you look at these boards showing what is the fare to go where you want to go...

|

| Destination and fare board at Kooriyama station |

3- The same trains serve both local trips and regional trips

There are expresses, but in many cases, trains stop at all station, even when some are within the same city. This allows regional trains with lines going on for 100 km or more (60 miles) to also be useful for commuters within cities they go across. It's the same train, the same fares apply and it helps to increase ridership for no additional cost as the same service serves both as commuter rail and as regional rail.... just like highways are currently used both by commuters and by long-distance travelers. Again, it means that people going farther out will be taking the same train they may use on their commutes, just stay on it a bit longer. It again helps to make taking the train a casual experience and it means that stations get all-day service, unlike commuter rail in North America that exists only 3 hours a day.

4- Since the rail exists, development grows along the rail lines

This is a bit different from the others as it's not about consumer service per se, but it is very relevant here in keeping areas connected. When cities sprawl in North America, they generally do so beyond the reach of their structural rapid transit system (at least, where it even exists). Developments therefore follow highways to keep a transport connection to the rest of the metropolitan area. In Japan, because regional rail extends far beyond the limits of current metropolitan developments, new developments can follow rail rather than highways.Let's do this visually, let's take a North American city with both highways and LRT or subways in the central city:

|

| A North American city, the urban area is in grey, highways are the black solid lines, rapid transit is the dotted red lines |

|

| In yellow, the new developments, concentrated along highways |

Now, let's take a Japanese city, where highways skirt around urban areas and rail lines with constant train service cross the area.

Where will new developments occur? In this case, both rail and highways exist in undeveloped areas, but rail connections lead directly to the downtown area, not highways. So new developments will follow the rail lines that already exist:

These new developments will start with decent, fast rapid transit service to the city from day one. Which will shape the form they take and allows most destinations, even the more recent ones, to reliably be within reach of the rail system.

Bringing this freedom of mobility to North America

OK, the Japanese have us beat, now, can we import this model?Some would say that we don't have the rail system to do so and it would be expensive to build one... except the truth is North America already has rail lines connecting most cities. Most North American cities built from the 19th century onwards were built along railroads. There is a lot of under-used rail lines or ROW in North America, rebuilding a regional rail system could be largely done by reactivating unused or under-used rail lines. The biggest issues in doing so is that rail lines have been given over to freight train companies which jealously defend their priority on the lines. Personally, I'm of the mind that ownership of the tracks and of train companies should be separated. Currently, freight train companies aren't interested in optimal use of tracks, because doing so would impact their number one business: carrying freight. Passenger rail can then only exist within the holes of freight schedules. The best solution would be to either legally impose the separation of track and train business, so the track owners would prefer to allow as many trains on their tracks rather than favoring one customer over the other, or simply nationalizing tracks (which appeals to my socialist side). The UK and France have this model currently.

The current rail system in North America is like if we allowed freight truck companies to buy highways, and they would then forbid their competitors on them and put quotas on the number of vehicles that could use their highways so as to preserve speed for their own trucks. It would be disastrous for highway capacity and highway-dependent developments... just like the current system is horrible for transit.

Amtrak and VIA would also have to revise completely how they deliver service and end this completely stupid artificial separation between long-distance trips and commuter service. Both can and should be served by the exact same lines.

Some would say still that this is too hard, that we should use the highways we have instead and run buses instead of trains.

Now, the big problem of transit piggybacking off of car-oriented infrastructure is that it is piggybacking off of car-oriented infrastructure. Meaning that the areas that are most readily accessible are car-oriented areas where people get dropped off in huge parking lots far from density and walkable areas. For example, here is a bus stop that I used recently on a vacation in Mont-Tremblant when I decided to take the bus.

Yes, that is just a gas station, without any sign that buses stop there or that you can buy bus tickets there. Why there rather than another gas station? Probably because it's closest to the highway, but how could someone who has never taken the bus know that it's where regional buses stop? They can't unless they do a search on the 'net. And the core of the village is a good 2 kilometers away from this gas station. And there is no information about where you can go anywhere.

Everything that made the train stations in Japan attractive and gave a feeling that you can go places easily is lacking here. The area is not walkable, nor near the downtown area, the area where the network can be accessed is not easily identifiable, and there is no feeling that you are even accessing a NETWORK, you only know there is a bus route, but you don't know anything about it and the network it is a part of. It feels like an ad hoc service, not a real national network of car-less mobility.

Can this be corrected? Probably not, because going to the downtown area in buses at every stop would slow down the service so terribly that it would be completely uncompetitive with cars, whereas trains in Japan are frequently as fast or faster than cars, even the regional trains, since they have exclusive ROW all the way from station to station. Buses can work but only if they act like airplanes: taking you from one bus terminal in the downtown of a big city to another bus terminal in the downtown of another big city, with few or no stops in between, putting off-limits all the areas you travel through.

Conclusion

I think it is important to think about regional mobility without cars, to offer a national transport infrastructure that can link up cities all over the country and tie walkable areas together. This is sorely lacking in North America, there is no such system, though there used to be (because we subsidized its direct competitor, highways, and pushed it to bankruptcy). Otherwise, no matter how good places we build, even if there is decent city transit, it will still feel like a golden cage to people getting around without cars. True freedom of mobility is dependent on a complete train system that is reliable, easily accessible and can easily serve both to go 500 km or to go 10 km away to the next town over.Such a system also creates a backbone along which development can occur rather than having it sprawl along highways. It's not that most people will use these trains frequently, they may not, but the important thing is: it is there, and people know that it is there and they can depend on it to go almost anywhere they want.