In North America, one frequent advice people receive is not to rent, because that money is lost, whereas owning a house is an investment that will not be lost. To an extreme, some people even bought houses or condos just for investment purposes, something that contributed largely to the housing bubble in the United States a few years back. But even with the bursting of the housing bubble, people still claim that houses are good investment prospects.

However, there is a counter-example to the idea that houses always appreciate: Japan.

In Japan, house-building is completely different. In North America, most houses are built by companies at one time when they build an entire subdivision, then sell the houses to people. In Japan, many if not most houses are built by people actually buying or renting a lot, then hiring a construction company to build their house for them. This is possible largely because Japanese planning is much friendlier to piecemeal constructions than in America or Europe.

But the main difference is what happens to house prices. They drop over the years, pretty fast even, and most people accept that the house they build will not be worth much in 20 or 30 years. In some cases, the house's value is even negative, people will offer buyers to destroy the house for them, at a price.

How can we reconcile these two attitudes on an economic point of view?

Now, it's true that a good's value ultimately is whatever people are ready to pay for it. But in the long run, prices tend to have rational explanations. For example, in determining the cost of a house near a vacant lot, the value of that house ultimately will depend on the cost of building a similar house on the vacant lot next door. If the seller demands more money than the cost of acquiring the land and building a similar house, then people will opt for that instead of buying the current house. Is it possible that both the North American and Japanese approach may exist in fact in the same economic reality?

Price of house vs price of land

First things first, my understanding of house prices is that they are actually the sum of two things:

1- The price of the building itself

2- The price of the land

I think essentially the only reason why house prices tend to appreciate over the years is not the price of the building, but the price of the land. Unlike houses, you cannot build land, land is a fixed supply. So when an area is desirable and you have run out of land to build on, the land becomes rare, and so it becomes more expensive. Even in sprawl, this has an effect, all inner suburbs were once outer suburbs, so as sprawl extends, unbuilt areas nearest to the downtown area become rarer until they essentially disappear. So the only land available to purchase is the land that comes with houses already built on them as some people move away and have to sell their homes. This creates a shortage of land and drives the land prices up. Unless you make old neighborhoods so undesirable that people no longer want to live there in general, which typically occurs when people put freeways in old neighborhoods, cutting off the community from itself and from the neighboring area.

Speculation, which creates an artificial shortage of land as speculators hold them to push their prices up, may also have the same result on land prices even when there are unbuilt areas around.

So the reality is that the small Vancouver house worth 1 million dollars isn't worth it due to the house itself, but due to the land it's sitting on, which is highly desirable. If you offered to sell the house for 1 million dollars, but once the sale is done, you removed the house to a location of the buyer's choice and kept the land, no one would take you up on your offer. The house itself is likely only worth 100 000 or 150 000$, which is the replacement cost of the structure.

This effect can be compensated by higher density, which zoning often bans, condemning desirable areas to housing shortages. But even if you allow density, the higher density allowed still means that land prices are likely to have higher value per square foot of land... higher density just dilutes this higher land cost through many units, retaining housing affordability.

This effect can be compensated by higher density, which zoning often bans, condemning desirable areas to housing shortages. But even if you allow density, the higher density allowed still means that land prices are likely to have higher value per square foot of land... higher density just dilutes this higher land cost through many units, retaining housing affordability.

Buildings' value naturally depreciates

Contrary to popular opinion, I don't think houses actually appreciate. They are not special. In life, most durable goods depreciate as time take its toll on them. That's true of everything, like roads, railroad tracks, vehicles, etc... But that doesn't mean that value always ends up at zero, no, the value of many of these goods gets reinforced by more spending on them. We fix roads, replace railroad ties, repair cars, etc... This money is injected into these durable goods to maintain their quality or sometimes even to improve them and increase their value.

It's basic accounting. When you buy a durable good, you don't lose the money, you simply transfer the value from a liquid good (money) to an immobile asset (house in this case). Over the years, the asset can either appreciate or depreciate, and any injection of funds to repair it or make it better results in an increase in the value of that good.

So if you have an house that is worth 200 000$ and build an extension for 30 000$, then your house, according to accounting practices, should be now worth 230 000$.

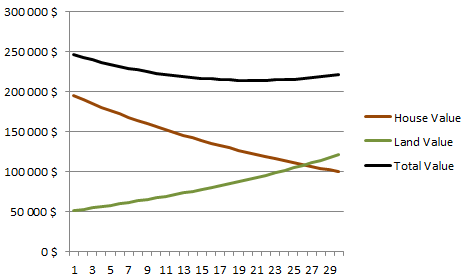

So let's take an example of an house bought for 250 000$, 200 000$ for the house itself, 50 000$ for the land. The owner pays 2 000$ per year on average on various maintenance and repairs, which helps maintain the house's value, and spends 15 000$ every 10 years as a big project (kitchen remodeling, adding a pool, building a concrete porch in the backyard, etc...). In the meanwhile, the house itself depreciates at 3% every year while the land appreciates by 3% every years as the area gets built up and land becomes rarer and rarer. I suppose 0% inflation.

Here is what the house value looks like according to a standard accounting model:

|

| House value |

Here is what the land value looks like:

|

| Land value |

And finally, the sum of these two values:

|

| Total value over time |

Overall, there has been an appreciation, but all of it comes from the land. The house value, despite significant improvements, has still fallen over the years. The total cost, house and land, was 250 000$ and the final value was about 275 000$, a gain of 25 000$. However, over the years, the home owner spent an additional 105 000$ on maintenance and improvements, for a real total cost of 355 000$, and a loss of 80 000$.

For example, I'll take my parents' house. Bought in 1978 for 75 000$ (around 250 000$ in 2014 money), it used to have an unfinished basement, a small balcony in wood in the backyard and no pool. Over the years, my parents spent tens of thousands of dollars having the basement finished, having an in-ground pool dug and built, remodeling the kitchen and toilets and replacing the backyard balcony with a large concrete porch, I'm not talking of the regular maintenance here. Overall, my mother told me they have put about 150 000$ in various renovations. The house is now evaluated at around 350 000$, which is less than the sum of the initial price and all the money put into renovations, once adjusted for inflation.

Another empirical proof of this is that new buildings in expensive areas tend to be more expensive than old buildings, all else being equal. Having a new home over an old one tends to be viewed as a good thing, the new one will be more modern and have more amenities and will be less likely to require repairs in the next few years. An old high class building can still be worth more than a recent shoddy construction, but that's an exception, not the rule, and a new high class building would probably be more expensive.

Another empirical proof of this is that new buildings in expensive areas tend to be more expensive than old buildings, all else being equal. Having a new home over an old one tends to be viewed as a good thing, the new one will be more modern and have more amenities and will be less likely to require repairs in the next few years. An old high class building can still be worth more than a recent shoddy construction, but that's an exception, not the rule, and a new high class building would probably be more expensive.

The Japanese attitude on the other hand is to initially build the house you want, then do the minimal upkeep, without remodeling and renovating the house significantly. So let's simulate what this looks like, same 3% depreciation for the house and 3% appreciation for the land, same 200 000$ value for the house and 50 000$ value for the land, but just 1 000$ in yearly maintenance and no major remodeling.

This is what it looks like:

|

| House value |

|

| Land value |

|

| Total value |

Overall, that Japanese attitude results in a depreciation of the total value to about 220 000$, a loss of 30 000$ which hides a significant appreciation of the land and a significant depreciation of the house. However, the total cost over the years to the homeowner has been only 280 000$. So the homeowner has actually lost less money in the house, only 60 000$ versus 80 000$ for the first guy.

So the Japanese example does make sense economically speaking. Culture still intervenes at another level, house depreciation may be higher, 5 or 6%, in Japan.

This dynamic exists also in the North American market, with

the so-called "fixer upper": an house that has not been maintained and

remodeled enough and which value is significantly below that of

neighboring houses, but which requires significant work done to recover

its value.

One factor that also has to be considered is that Japan was really not a rich country in the 50s and 60s. Housing built in that period was often very, very poor. Images of old apartments and houses I've seen on Japanese real estate sites (suumo.jp is a good one if you can read Japanese a bit) are completely disastrous. Houses were really built to a lower standard and so destroying and rebuilding was probably cheaper than overhauling the current house.

Conclusion

I think in general we have to assume that houses are depreciating goods, just depreciating at a slower rate than many other goods, like cars for instance. However, land (at least in growing cities) appreciates and can result in total value increasing if the rate of appreciation of the land is higher than the depreciation of the building itself. Houses in general are poor investment prospects as the cost of maintaining its value will generally eliminate most gains in its market value, unless one can renovate the house themselves and flip it after upgrading it. An exception to this is places where land appreciates very, very quickly, which may be the result of land shortages.

In terms of urban development, this is important to understand because when people see houses as investments and as appreciating goods, they tend to be hostile to any policies allowing their replacement. As the buildings are seen as valuable, destroying them is seen as little short of heretical. People need to understand it's not the building itself that is a wise investment product, but the land on which the house is built. Once we see buildings as essentially depreciating goods, I think we become more pragmatic about them, and understand that protecting buildings by preventing built areas from changing is not actually a wise course of action, at least on economic grounds.

In some ways, the North American approach of preventing housing from being torn down and instead renovating old houses over and over is a bit like the Cubans who, because of the embargo, kept the cars of the 50s they had and just kept rebuilding them over and over, replacing them part by part as they fail, since they couldn't get newer replacements. It may be great for classic American car lovers, but it still results in highly-polluting death traps traveling on the roads, when modern cars would be better for the environment and be much safer for people both inside and outside the vehicle.

In terms of urban development, this is important to understand because when people see houses as investments and as appreciating goods, they tend to be hostile to any policies allowing their replacement. As the buildings are seen as valuable, destroying them is seen as little short of heretical. People need to understand it's not the building itself that is a wise investment product, but the land on which the house is built. Once we see buildings as essentially depreciating goods, I think we become more pragmatic about them, and understand that protecting buildings by preventing built areas from changing is not actually a wise course of action, at least on economic grounds.

In some ways, the North American approach of preventing housing from being torn down and instead renovating old houses over and over is a bit like the Cubans who, because of the embargo, kept the cars of the 50s they had and just kept rebuilding them over and over, replacing them part by part as they fail, since they couldn't get newer replacements. It may be great for classic American car lovers, but it still results in highly-polluting death traps traveling on the roads, when modern cars would be better for the environment and be much safer for people both inside and outside the vehicle.

No comments:

Post a Comment