So, the Cato Institute is at it again, this time with a "study" by noted anti-rail activist Randal O'Toole which claims that light rail is a waste of money and that a system of "rapid buses" would offer more speed and better service at a lower cost.

You can find the study here:

http://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/rapid-bus-low-cost-high-capacity-transit-system-major-urban-areas

I feel a need to point out how wrong it is. So, here goes.

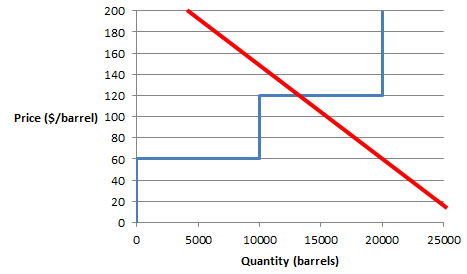

First, here is the schematic system he devised:

|

| O'Toole's rapid bus system |

So basically there are two freeways, one north-south, the other east-west. Buses with high frequency would travel along major arterials with one stop per half-mile, then join the freeway (where they have a bus lane) where they would continue without stopping up to the downtown area and drop off people there. I now it's without stopping because he clearly states that buses will travel 60 mph on average on the freeway, which is impossible if buses have to stop at each interchange.

If buses stopped at each interchange, as just stopping and accelerating back again to 60 mph would take a good minute or so, if there was an interchange every mile, the average speed would fall to 30 mph, even more once we account for the lack of stations on the freeway, which would mean bus drivers would have to exit the highway, drop off people, then go back on it.

In the downtown area, regular buses on major streets would distribute people in the CBD.

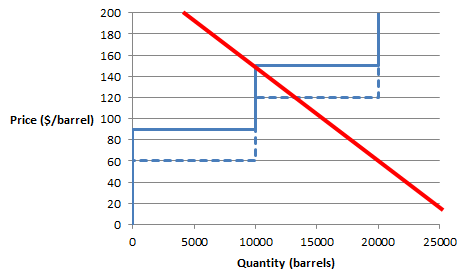

In comparing to a 4-line LRT, I'm guessing he takes the same city and just says the freeways are the LRTs, something a bit like this:

|

| Supposed 4 LRT line system (could actually be 2 lines, but whatever) |

So, now that we have established this, let's get started on his "mistakes".

Mistake 1: The LRT system serves less of the urban area

Wrong. The LRT offers BETTER service of the urban area than his "rapid bus" system. Though LRT are adjacent to less of the city than buses, the LRT system would still include feeder buses which would work the exact same way the buses work in his system, meaning half-mile stops on arterials, taking people to the LRT stations instead of following the freeway. So overall, just as much of the area is covered by the system, with buses filling the gaps. No rail proponent ever argues for dropping buses completely.

So why do I say it is actually better service on the LRT?

Well, let's say I am on point A and want to go to point B that is not in the CBD:

You have no choice but to do this trip: to take a bus into downtown, then another one in the other direction, which is a lot of wasted miles and time.

In an LRT system, as the LRT stops at stations along the way, you can simply get off at the closest station and walk or take a short bus trip to your destination. To illustrate visually what this means, let me show you the "transitshed" of point A, the areas that are acceptably close to point A in transit:

|

| The green zone is the places that people on point A can easily reach, with a rail system |

|

| Now this is the same thing but with the "rapid bus system" |

The reality is that the express bus system pushed by O'Toole ensures quick trips to the downtown area, but makes the rest of the city nearly unreachable without going through the downtown and making huge detours. This means that the CBD will be dense, but everywhere else will be sprawl because of poor transit access, meanwhile, dense TOD developments can spring up around all stations in the LRT system.

That's the big problem with expresses, they are fast, but not flexible at all. They take you one place only, and if you're not going there, too bad.

Mistake 2:A LRT system has less capacity than a bus system

O'Toole makes the claim that his bus system has a capacity of 140 000 passengers per hour, versus only 36 000 for a 4-line LRT system. This is a classic example of comparing a theoretical maximum (the 140 000 pphd number) for buses and a practical maximum for LRT.

It is true that on a freeway lane, buses' capacity can be sky-high, if buses don't have to stop, they can follow each other closely, get insane frequency of hundreds of buses per hour. However, there's a big if: IF THEY DO NOT STOP. Again, this is a weakness with express buses. The reality is that the capacity of the system is not really comparable, because the trunk isn't really serviced by any bus, but rather has many lines traveling on the same lane that have nothing to do with each other, each line having much lower capacity than the sum of the lines.

|

| Each line here has a capacity of 10 000 pphd, together they would be 20 000 pphd, but the reality is that they don't connect, so the capacities cannot be added together |

So in this case, if the blue line has a demand of 13 000 people and the red one of 7 000 people, in practice, the blue line would be significantly overcapacity, the red line would be under capacity. Only 17 000 people will go through in an hour. In practice, on such trunk lines, there will be full buses and half-empty buses.

Meanwhile, a rail line has a real capacity along the line, as every trip takes the same line, it really offers the nominal capacity. Some rail lines do reach their nominal capacity, even go above it. The way rapid rail transit works is much better at maximizing capacity utilization. Especially in off-peak times, a bus system will either have terrible frequencies or buses will be near empty, whereas a rail system can maintain decent frequency (below 10 minutes) with a decent amount of people per vehicle.

Furthermore, he presumed a capacity of 9 000 passengers per hour for LRT, which is not the true maximum capacity of LRT. Theoretically, an LRT line on a grade-separated right-of-way like freeway medians can have trains of 4 cars each with a capacity of 250 passengers at a frequency of 30 trains per hour. That is about 30 000 pphd capacity. Heavy rail lines can have even more, the Yamanote line in Tokyo carries more than 80 000 pphd.

So once we compare theoretical maximum with theoretical maximum, both systems offer the same capacity, more or less.

Mistake 3:The operating costs of the bus system would be less than that of the LRT system

That one is just plain insane. The reality is that rail has an insurmountable advantage in terms of operating cost versus buses for a very simple reason: 30 to 50% of the cost of running transit is sitting behind the steering wheel. So the more people a single driver can carry in his vehicle, the lower the operating costs will be.

Rail transit has a major advantage because as it is on guided railways, it can easily tie up many cars one behind the other and the cars themselves may be longer. All with little to no effect on the quality of the ride. Furthermore, train running also reduces wind drag and steel wheels on rails have less friction than rubber on asphalt or concrete, meaning that trains are more efficient in terms of energy. Of course, if you run empty trains, that advantage is negated, but for near-capacity running, there's not even any debate.

OK, caveat time. If a rail system uses short cars and doesn't put them in trains so it has no more capacity per vehicle than buses, then the operating costs may be higher because of the need to maintain the tracks (looking at you Toronto, the Bombardier Flexity cannot come too soon). Buses scrap roadways horribly, but generally the maintenance of roadways is shared with cars and not directly assumed by the transit operator.

Anyway, that's why OC Transpo in Ottawa spends 3,80$ per passenger to provide service, versus 3,10$ for the STM in Montréal, despite trips being longer in Montréal, and 3,01$ for Calgary Transit. OC Transpo relies on a BRT system with a lot of buses running alongside it, the STM has a subway system instead, Calgary has the C-train LRT.

And that's why Ottawa is converting its BRT into LRT, increasing capacity and lowering operating costs by tens of millions of dollars per year. Transit operators know that O'Toole's claim that buses have lower operating costs is bullshit.

Trains are also more reliable, for instance, the mean distance between breakdown of buses in Calgary Transit's fleet in 2012 is 7 200 km, for LRT cars, it's 72 100 km. They last longer, with an average lifespan of 30 years versus 10-15 for buses.

Mistake 4: ignoring qualitative service differences

Time after time, it is confirmed that people prefer rail's ride to buses. Rail is more comfortable and more pleasant to use, for two well-maintained systems, rail will give the impression of gliding along, while buses will still bounce around.

So even if the capacity is the same quantitatively, as rail-based systems are more likely to draw in more riders, the costs of the system will be spread among more riders and thus be lower than if both systems had the same ridership. And that's what defines an efficient system, the cost per passenger, not the total cost.

Mistake 5: the issue of the bus terminal

At a capacity of 140 000 passengers per hour, it would mean nearly 1 200 articulated buses coming into downtown every hour during the peak and an equivalent number going out. In general, expresses tend to go to a few terminals. If all this traffic came into one terminal, assuming it may take 2 minutes to unload a bus, it would mean the terminal should have enough places to accommodate at least 40 buses at the same time, just on the arrival deck, even more on the departure side. Do you have any idea how big that would be? The Port Authority Bus terminal in New York has 225 000 passengers per day, which is probably a third of the capacity needed for the bus terminal for this proposal. From Google Maps, it looks like it takes about 10 acres of space, nearly two entire New York City blocks on its own.

Then, there is the issue of getting buses there on local streets, if that number of buses could fit into a free-flowing freeway lane, on a single urban street, that is much less sure.

Oh, you could split up the buses and have different lines ending at different terminals, which would reduce the effective frequency of service for users. The more lines you create with different destinations, the more you reduce the frequency of each line. For the average user, what's the point of having a bus pass every 20 seconds if only one in 10 minutes gets him where he wants to go? The other buses don't exist for him.

Furthermore, there is the problem of proximity. Very few places will be within walking distance of the bus terminus, and transit from it will take place on surface buses traveling at 8-10 mph, greatly limiting the effective range of transit.

Furthermore, there is the problem of proximity. Very few places will be within walking distance of the bus terminus, and transit from it will take place on surface buses traveling at 8-10 mph, greatly limiting the effective range of transit.

In Montréal, we have a similar rapid bus system on the Champlain bridge (which is supposed to be converted to LRT one day, though the anti-rail lobby is mounting an offensive against it) and it's considered nearing capacity even though it carries only 20 000 people during the AM peak (all 3 hours of it). It takes people to a downtown bus terminal. But if there was just this bus terminal and that's it, it would be poorly used because it would take an eternity to get a bit further out of the downtown area in buses, as buses around there crawl at 8-12 km/h (5-8 mph) and have low capacity for every line. What allows this terminal to thrive is the subway system which allows all these people to reach their destinations quickly all over the city, at least to the areas connected to the subway, at speeds between 30 and 40 km/h (20 to 26 mph).

Such rapid bus trunks can be useful, but if it is supported by a tightly knit rapid transit system with great capacity and speed. If they are supported only by slow local buses, no matter how frequent, they have a much reduced potential and make only a small part of the downtown area transit-accessible.

I could probably go on, but I think I'm done with this. The point to remember is that the Cato Institute and Randal O'Toole are essentially professional liars for hire. They get paid to dress up in simili-logical reasons why we should all support the policies that make their donors much, much richer. They are not to be trusted.