In general in North America,there is largely two cases determining when rapid transit investments are done

1- In places that are already pretty dense and where demand for transit is so high that it overwhelms the local transit lines. Rapid transit here serves to increase the capacity and quality of transit where transit is already highly justified.

2- In places where there are chokepoints (often natural due to large rivers splitting an urban area in many parts) that make increasing road capacity outrageously expensive, then rapid transit is used to support the downtown area by increasing the capacity of transport links without having to build new roads or widen existing ones.

In terms of what form they will take, in the first case it usually takes the form of subways built to serve old streetcar suburbs which already have high density and not that many parking spots. The second will usually be commuter rail or light rail lines extending far beyond the city core, often with stations surrounded by huge expanses of parking, so that residents of low-density neighborhoods can park at the station then ride the rest of the way. In order to save on the capital costs, they will often use existing rail lines or be built in a freeway alignment.

|

| Subway station Mont-Royal in Montréal, in an old streetcar suburb |

What is the problem?

The problem is that this way of planning transit is merely reactive, reacting to development patterns. In terms of direct ridership potential, the first approach is certainly the better, yet it is available in only a few areas, essentially older, denser neighborhoods with mixed uses. The latter is cheaper but has low potential for ridership, at least as things stand. Both approaches ignore the very significant influence that the presence of a rapid transit line can have on developments. Sure, transit-oriented developments can follow, but it's often an uphill battle.

The point that is important to understand is that high-capacity rapid transit is not only a transport tool, it is a powerful land use tool which task can be to shape cities and their development pattern.

The problem is that as we use highways to tie in cities together, development flows along on highways and other roads, the resulting development is then of course car-oriented because only cars are viable transport modes when areas develop. Later on, we try to add transit to it, but areas built for cars tend to have low density and to spread apart destinations rather than concentrating them, so car-oriented suburbs will not offer a lot of potential for transit.

So how can we convert our cities to make them transit-friendly? By changing them. When a rapid transit line comes in an area, there must be an understanding that the area within 800 - 1 000 meters (half a mile) of the stations WILL change and densify significantly. The area around must be replaced, what was adequate for car-dependent sprawl will not be adequate once there is a subway station. This is where euclidean zoning hurts the most as it is extremely hard to change, so does the idea that once an area is built, it should NEVER change, which is unfortunately too common both on the right and on the left.

The ridership gain potential from transit investment is mostly dependent on how much development transit can attract, not by convincing people who used to drive to take transit.

I spoke of streetcar suburbs recently, and the point that is most important to understand is that the transit line was built BEFORE the suburbs were built. That is why streetcar suburbs are such good TOD, it's because there was a transit line when the area was developed, so developments took the transit line in consideration. Just like right now industrial parks and malls are built around highway interchanges, at the time, industries and businesses flocked to the streetcar line, so as to be easy to access.

One thing that could be done is to simply build rapid transit prior to developments. People often think rapid transit is very expensive to build, but that's not really the case. Overall, rapid transit is less expensive than highways to build, laying tracks is no harder than building an highway. If subways are so expensive, it's largely because they are generally built underground (which is very expensive) and only in areas that are mostly all built-out already, which makes surface lines hard and expensive to build. You could theoretically use eminent domain to carve a narrow corridor through inhabited areas for the purpose of building rail through, but that would be quite hard to do politically, and still pretty expensive.

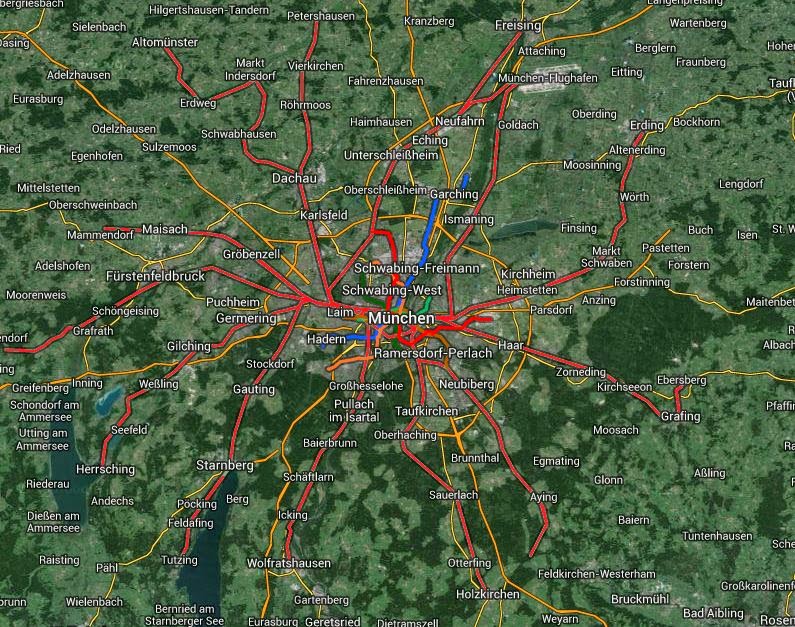

As you can see from the previous image, the S-bahn lines go far into the suburbs and connect them to the central city. The diameter of this web is around 70 kilometers, around 45 miles. That is nearly twice the diameter of the area covered by the New York subway. The system has about 445 kilometers of lines in total, about 280 miles, which is more than the 337 kilometers of lines of the New York subway (around 200 miles), for a population that is 6 times less (10 times less if you count the entire metropolitan areas of both). And this doesn't include the subway, because Munich has subways too, and some regional train lines. Of course, the lines don't have the same capacity as the New York subway, but they do offer quite similar service in terms of speed and comfort for users.

In this image, we can see small suburbs of Munich, with an highway on the bottom of the image and the S-bahn going through the center of these towns. Often, shopping streets will be within walking distance of the S-bahn stations rather than being malls next to the highway.

How can Munich afford this? The S-bahn lines run on the surface in the suburbs, which makes them especially cheap to build, no more expensive than the highways and major roads on which North American suburbs depend. Their presence in growing suburbs attract developments near them, which feeds the system well.

The problem is that as we use highways to tie in cities together, development flows along on highways and other roads, the resulting development is then of course car-oriented because only cars are viable transport modes when areas develop. Later on, we try to add transit to it, but areas built for cars tend to have low density and to spread apart destinations rather than concentrating them, so car-oriented suburbs will not offer a lot of potential for transit.

So how can we convert our cities to make them transit-friendly? By changing them. When a rapid transit line comes in an area, there must be an understanding that the area within 800 - 1 000 meters (half a mile) of the stations WILL change and densify significantly. The area around must be replaced, what was adequate for car-dependent sprawl will not be adequate once there is a subway station. This is where euclidean zoning hurts the most as it is extremely hard to change, so does the idea that once an area is built, it should NEVER change, which is unfortunately too common both on the right and on the left.

The ridership gain potential from transit investment is mostly dependent on how much development transit can attract, not by convincing people who used to drive to take transit.

I spoke of streetcar suburbs recently, and the point that is most important to understand is that the transit line was built BEFORE the suburbs were built. That is why streetcar suburbs are such good TOD, it's because there was a transit line when the area was developed, so developments took the transit line in consideration. Just like right now industrial parks and malls are built around highway interchanges, at the time, industries and businesses flocked to the streetcar line, so as to be easy to access.

One thing that could be done is to simply build rapid transit prior to developments. People often think rapid transit is very expensive to build, but that's not really the case. Overall, rapid transit is less expensive than highways to build, laying tracks is no harder than building an highway. If subways are so expensive, it's largely because they are generally built underground (which is very expensive) and only in areas that are mostly all built-out already, which makes surface lines hard and expensive to build. You could theoretically use eminent domain to carve a narrow corridor through inhabited areas for the purpose of building rail through, but that would be quite hard to do politically, and still pretty expensive.

Example: Munich's S-bahns

Munich, like many other German cities, has an extremely well-developed transit network. One of the most interesting aspects of it is the S-bahn network. S-bahn are essentially light-rail lines that run on grade-separated tracks outside cities and on streets in the city. In France, they would be called "tram-trains". |

| The spiderweb of red lines on this map of Munich are the S-bahn lines |

|

| The dark green line is the S-bahn, the S symbols are the stations |

How can Munich afford this? The S-bahn lines run on the surface in the suburbs, which makes them especially cheap to build, no more expensive than the highways and major roads on which North American suburbs depend. Their presence in growing suburbs attract developments near them, which feeds the system well.

Other example: Chigasaki

Here is another example of a surface line attracting developments, a Tokyo suburb this time, Chigasaki station, on the Tokaido line. The Tokaido line is actually a regional train line 714-kilometer long (443 miles), but it doubles as commuter rail as it is just as easy taking the Tokaido line as taking a subway line. No need to buy a ticket beforehand for a given departure time and hand it to a staff member prior to boarding (like Amtrak and Via Rail do, imitating airlines... because when thinking about user experience, airlines are the best example that came to their minds apparently!).

Anyway, here is what Chigasaki's train station looks like:

The station is the huge white building in the background. Why is it so big? Because it includes many stores inside it. The letters in blue spell out "Lusca", which appears to be the name of a company making shopping centers if I understand correctly. There is a pedestrian plaza built over the street on huge walkways, which I have also seen in other places like Sendai. This frees up the ground area for a bus terminal and taxi parking, as you can see plenty of buses in the lower right corner of the image.

You can also notice plenty of tall buildings around the station, these are also stores and restaurants, and some offices, all concentrated around the station.

Just like I did for the Plateau, let me show you the results of a search for "mise" (store) on Google Maps around Chigasaki station.

Note how the stores are massively concentrated around the station and the streets leading to it. This is supremely convenient for transit users, when they arrive at the station in the morning and they want a coffee, there are plenty of restaurants to choose from on the way to the station. When they come back home in the evening and they have to buy a few groceries, they can easily do so, it's on their way. That's how it works too in freeway-oriented developments, stores flock to freeway exits to be "on the way" of commuters taking the freeway or getting off of it.

Here is an example of some of the streets leading to the station, the smaller ones in particular.

What about housing? Well, there is high-density housing, but overall, priority is given to businesses, not housing.

Here are three pictures of a street near the station and how it changes as one walks further away. First, right next to the station, there are shops...

...then, you come to residential towers of some height...

...and finally, on the side streets, you have single-family housing.

All of this within walking distance of the station.

This is what TODs look like, proper TODs. Though not every station is built the same way, each 2 or 3 stations, you will come over something like this in Tokyo's suburbs. So when building transit stations in built out areas, it is important to allow developments that look a bit like this. And it's important to include not just proximity stores like corner stores, but to have specialized stores in malls or big shopping areas once in a while around stations, attracting big brands if possible. That way, people living near the line may be tempted to use it to go shopping rather than just going to work, they're no longer forced to go to big malls on the outskirts for their specialized shopping.

I think too often even people who are generally allies of urbanism shirk at allowing this kind of development, they seek to preserve "character" and "mom and pop stores" by keeping big stores away from neighborhoods. But this is counter-productive, because by keeping the big stores from settling near transit, they just move to the suburbs, and then a lot of people start taking cars to them.

Rapid transit investments need to be accompanied by significant relaxation of zoning so as to allow development to flood the transit stations. A new transit station must not merely be an added bonus for current residents who happen to live near, it must herald major changes and increased density, else, the money is almost wasted. Increase in ridership will come when people and businesses move to the area, not when previous residents living in car-oriented development start to abandon their cars to take transit.

In fact, if you feel daring, using eminent domain to appropriate low-density areas before the line is built, then re-selling the land after to developers may well serve to pay part of the line's construction. This is called "value capture". There are other ways of doing it, like special local taxes on properties that see their values increase, but these taxes often have a counter-productive effect of discouraging development in areas subjected to this extra "value capture" tax.

It is best also to plan for transit BEFORE areas are built out and to extend rapid transit lines to the suburbs as quickly as possible, as building tracks in undeveloped areas is no more expensive than building roads there. It is easier to influence the built form of an area when it is being built than to transform a fully developed area, and the housing in greenfield developments tends to be cheaper than in infill developments.

Anyway, here is what Chigasaki's train station looks like:

|

| Chigasaki station |

You can also notice plenty of tall buildings around the station, these are also stores and restaurants, and some offices, all concentrated around the station.

|

| Street that leads to Chigasaki station |

|

| Locations of stores in Chigasaki |

Here is an example of some of the streets leading to the station, the smaller ones in particular.

|

| Shopping street near Chigasaki station |

|

| South side of Chigasaki station, some tall residential towers with shops on the ground floor |

...then, you come to residential towers of some height...

...and finally, on the side streets, you have single-family housing.

All of this within walking distance of the station.

This is what TODs look like, proper TODs. Though not every station is built the same way, each 2 or 3 stations, you will come over something like this in Tokyo's suburbs. So when building transit stations in built out areas, it is important to allow developments that look a bit like this. And it's important to include not just proximity stores like corner stores, but to have specialized stores in malls or big shopping areas once in a while around stations, attracting big brands if possible. That way, people living near the line may be tempted to use it to go shopping rather than just going to work, they're no longer forced to go to big malls on the outskirts for their specialized shopping.

I think too often even people who are generally allies of urbanism shirk at allowing this kind of development, they seek to preserve "character" and "mom and pop stores" by keeping big stores away from neighborhoods. But this is counter-productive, because by keeping the big stores from settling near transit, they just move to the suburbs, and then a lot of people start taking cars to them.

In conclusion

Transit is not merely about transport, it is about shaping cities and influencing their development, especially high-capacity, high-speed transit.Rapid transit investments need to be accompanied by significant relaxation of zoning so as to allow development to flood the transit stations. A new transit station must not merely be an added bonus for current residents who happen to live near, it must herald major changes and increased density, else, the money is almost wasted. Increase in ridership will come when people and businesses move to the area, not when previous residents living in car-oriented development start to abandon their cars to take transit.

In fact, if you feel daring, using eminent domain to appropriate low-density areas before the line is built, then re-selling the land after to developers may well serve to pay part of the line's construction. This is called "value capture". There are other ways of doing it, like special local taxes on properties that see their values increase, but these taxes often have a counter-productive effect of discouraging development in areas subjected to this extra "value capture" tax.

It is best also to plan for transit BEFORE areas are built out and to extend rapid transit lines to the suburbs as quickly as possible, as building tracks in undeveloped areas is no more expensive than building roads there. It is easier to influence the built form of an area when it is being built than to transform a fully developed area, and the housing in greenfield developments tends to be cheaper than in infill developments.