Well, it's been a long while since my last post. A combination of a busy life, a feeling that I had said most of what I felt comfortable saying and a desire not to repeat myself contributed to this silence. That being said, I have just found something that inspired me to break my silence.

Note, in this blog, I will use metric, here are easy, rough conversion factors:

1 square meter = 11 square feet

3 meters = 10 feet

The modern mid-rise mini-boom

In most North American cities, a new type of building has started to emerge, generally designed to offer urban condos for young professionals in search of more urban housing accommodations. Due to the homogenization of the market, these often share architectural traits and similar look, leading to some protesting about their "cookie cutter" nature, being built in all cities without respecting the local vernacular architecture.

Here is just one article criticizing the style: Why America’s New Apartment Buildings All Look the Same

| ||

| If you live in a North American city, these will look familiar to you... no matter in what city you live |

Now, I'm not going to criticize them too much on the look, because:

- Every new architectural style created a backlash when it was introduced, before later on being cherished by the same who criticized them... see for example "browstone" buildings in New York, first seen as soulless atrocities, now absolutely beloved by architects and urbanists.

- These represent a new boom in urban housing that had been underdeveloped for decades, so I'm of the advice we shouldn't start objecting to something necessary just because it's not to the aesthetic taste of all.

That's not to say that this style of building is perfect, far from it. And this is why I'm writing this blog post, to criticize them for something I've yet to see addressed by most people, a problem of that style of development this is way more important than just aesthetic considerations and that I believe has major repercussions on the kind of housing provided by these new developments.

Without further ado... These new apartment buildings are just too fat!

Now that I have your attention, let me provide a few examples of apartment buildings in many different countries to illustrate the point.

Fit, slim modern and traditional apartment buildings around the world: providing family housing at urban densities

| |

| Haussmanian apartment buildings in Paris, the depth of the building measured here is 9,7 meters |

|

| Vienna traditional Euroblocs, depth of 12 meters |

|

| These more recent Euroblocs in Prague have a depth of 16 meters |

|

| Warsaw older apartment buildings, depth of 10 meters |

|

| Singapore, urban apartment buildings, depth of 12 meters |

|

| Project from Urban Renaissance in Tokyo, depth of 9 meters |

|

| Manshon projects in Sapporo's suburbs, depth of a bit less than 15 meters |

|

| Apartment buildings in Uppsala, a midsize Swedish city, depth of 14 meters |

|

| Boston's Methunion Manor coop buildings, depth of 11 meters |

Note that the depth of these buildings from Europe, Asia and North America, meant to provide accommodations to all kinds of households in urban (or even suburban) areas varies from 8 to 15 meters, with most being from 9 to 12 meters.

Now, let's look at some recent midrise condos in North American cities, shall we?

Fat, obese new urban apartment buildings of North America

|

| New condo buildings in the Griffintown neighborhood of Montréal, depth of 21 meters |

|

| Chicago, depth of 19 meters |

|

| Seattle, depth of 20 meters |

|

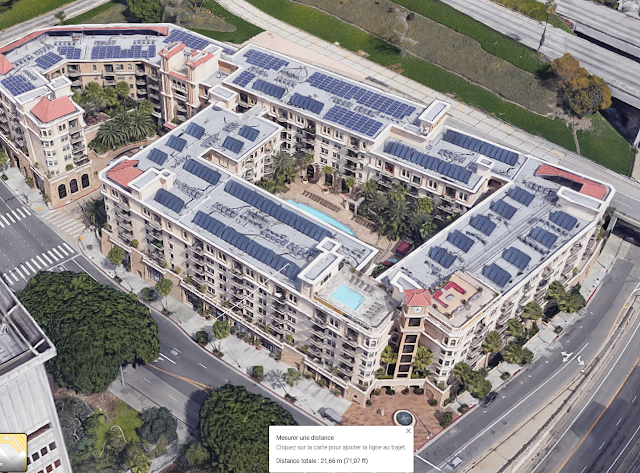

| Dallas, depth of 21 meters |

|

| Los Angeles, depth of nearly 22 meters |

There are just an handful of examples, but with your knowledge of your own city and Google Maps, I invite you to locate new developments and also measure the depth of these new developments. They tend to average around 20-22 meters.

Why it matters

So, now that I've hopefully provided enough proof of a difference between the "slim" apartment buildings of Europe, Asia and old North American developments and the "thick" apartment buildings of the current midrise urban housing boom, one might say:

"Well, ok, but what does it matter? Doesn't it just mean greater lot coverage and density for a given number of story?"

Well, yes it does mean greater lot coverage, but it does matter a lot if one's objective is to make sure all households can find accommodation in urban areas. That's because of windows. Either because of regulation or of market demand, it is generally accepted that two types of rooms in an unit require windows on the outside: bedrooms and the living room. The larger an household is, the more bedrooms they need, at least, according to modern living standards. So, families obviously require apartments with more bedrooms, one for the parents to share, and at least one bedroom for every two children (and ideally, if children have to share one bedroom, it should be bigger than if they each had their own bedroom).

So, the more bedrooms an unit has, the more exterior wall it must "consume". The floor area doesn't increase proportionally however, if a 1-bedroom unit for 2 people is about 60 square meters, a 2-bedroom unit for a family of 2 parents and 1 child with 70 or 75 square meters is sufficient, an increase of only about 20% to deal with a family that is 50% bigger. Likewise, a 3-bedroom unit can make do with 85-90 square meters, and accommodate a family with 2 or even 3 children.

To sum up easily, with basic North American urban standards:

Visually, let's look at the floor area consumption and the exterior wall consumption of these family types:

We can notice that the exterior wall consumed increases much faster than the floor area as families grow more numerous. This suggests a new metric that ought to be considered, the Floor-Area-to-Exterior-Wall ratio.

Let me calculate it for each family's preferred housing unit and for three types of apartment buildings, the slim traditional apartment building with a depth of 10 meters, the thick traditional apartment building with a depth of 15 meters and the modern obese apartment building with a depth of 20,5 meters. For simplicity's sake, I'll presume an infinitely long apartment, it won't change results much.

*****

ADDED ON 2020-01-14

Alon Levy on Twitter remarked that living space by person in the US tends to be significantly higher than the numbers I selected. It's true that I used minimum floor area sizes reflected in Montréal and a lot of cities with expensive real estate... what happens if I adjust the numbers a bit for higher to take that into account?

So even adjusting for bigger apartments, the conclusion remains the same. Now, luxury apartments or suburban apartments obviously go beyond that minimum, but I don't think these are relevant or typical of what could be build but cannot when buildings start getting too thick.

So even adjusting for bigger apartments, the conclusion remains the same. Now, luxury apartments or suburban apartments obviously go beyond that minimum, but I don't think these are relevant or typical of what could be build but cannot when buildings start getting too thick.

END OF ADDENDUM

*****

What this metric reveals is that the modern obese apartment building doesn't provide near enough exterior wall to provide the desired housing units of households with more than 2 people in them. As a result, if someone wants a 2-bedroom or a 3-bedroom unit, they are going to consume a lot more floor area than they would actually need. This has the consequence of increasing the cost of such units needlessly and by a lot.

For example, imagine you have a modern apartment building with a floor area to exterior wall ratio of 10,5, and you want to make sure all units in it have 2 bedrooms, then while these units would only need 72 square meters of floor area in a properly shaped building, you would be forced to provide each unit with around 95 square meters of floor area. That's nearly 30% more... and that also means that the cost will be 30% higher. So if you'd be able to make and sell 72-square meter units for 300 000$, the 95-square meter unit would need to sell for 400 000$ instead. That is prohibitively more expensive for a lot of people.

I could make geometrical explanations, but I think this is telling enough.

Consequences of obese apartment buildings

The result of this shape is that the vast majority of units in these new buildings are lofts or 1-bedroom units, and there are only rare 2-bedroom units or more, and they tend to be significantly more expensive than they ought to be. This makes families unable to profit from the recent boom in urban housing.

One could say that at least it responds a need, that's true, but this shape is pernicious because it can't be easily remedied. You can't easily reconfigure the interior of the apartment to accommodate more than 1-bedroom units. So you bake in a bias for these units for singles whenever you build these buildings. It's fine if it would be the occasional building, but it's too common for that. If we want to allow families to live in urban areas, we need to find a way to correct this.

Maybe we ought to implement regulation imposing a maximum ratio of floor area to exterior wall in new buildings.

Why it came about

My guess as to how it came about is that it's a result of zoning regulations and financial incentives. Most North American zoning regulations control the following:

- Front setback

- Back setback (the building can't extend to a certain distance of the property line in the back)

- Height limit

Meanwhile, most North American zoning regulations don't control FAR (floor area ratio), or when it does, it's not as strictly controlled as height and setbacks.

So, if you're a developer who wants to maximize profit (meaning, produce the highest floor area possible from a lot) and you have to respect strict setback rules and height limits, then the easy solution is to build a building that occupies all the lot you are legally allowed to build on and to build the maximum number of stories.

One problem is that once developers start doing that, then all lots are priced according to that approach that maximized FAR, and so developers who would use alternative shapes that reduce FAR but increase the possibility of family-sized units are punished financially by paying for a lot priced for a higher FAR than they can build. That cuts into their profits.

A solution would be stricter FAR control in regulation (to control lot prices) and looser height and setback regulations.

Approaches to maximize lot coverage and still offer a reasonable amount of exterior walls

These last examples are buildings that also seek to maximize lot

coverage while still taking into account the need for exterior walls to

provide family-sized housing units, through the use of peculiar forms

more complex than a simple rectangle.

| |

| Apartment buildings in Hong Kong, shaped like intersecting Hs, creating exterior walls between the arms of the building |

|

| New apartment buildings in Singapore, also using irregular shapes that look like the letter H, again, to maximize exterior walls and allow the production of more multi-bedroom units |

|

| This extremely deep apartment building in Madrid, Spain, has inner courtyards that reduce the effective depth of the building from 25 meters to just 12 meters |

|

| Some tests I made of different apartment building shapes and FAR per story of each, showing high lot coverage can be achieved while avoiding the obese apartment buildings we're building currently |

I've heard that one reason for the dimensions of American mid-rise apartments is that it maximizes the amount of parking that can fit underneath. I'll have to do some measurements on my building, but it would allow for 90° parking in two aisles, one on each side of the building centerline (though I think my building only really has parking under one side)

ReplyDeleteThe big block with inner courtyard(s) ('patio') from Madrid is, in fact, very characteristic of the Spanish urban boom of the 60s, 70s and 80s; you can find those designs all over the main metropolitan areas of the country. Thinner blocks without courtyard are sometimes present instead, but the kind of design you show in the post is quite representative of the 'desarrollismo' era. I know zilch about the building codes, but the extra windows provided by the courtyard are particularly important because, in most of Spain, clothes are generally hung outside a window to air-dry (tumble dryers are not widespread, as in the US).

ReplyDeleteMore modern developments (which are the subject of some urbanist criticism) often go instead for the rectangle block with one big inner courtyard that has space for a swimming pool, garden and/or sports courts. This picture ( https://i.imgur.com/UK59k2d.png ) from a Madrid suburb has a good comparison of both styles (70s south of the rail tracks, late 90s north of the train line). A few three-sided asterisk-shaped buildings too.

Interesting comment, thanks. I'll note however that even the modern buildings you point out still qualify as slim. Going on Google Maps, the ones without inner airshafts or courtyards are about only 12-13 meters deep, meanwhile, deeper buildings have small airshafts or interior alleys that reduce the effective depth of buildings.

Delete"This makes families unable to profit from the recent boom in urban housing."

ReplyDeleteHere's where I disagree.

The most common household size in America is a single person.

The most common (accounting for a plurality and about 40% of all units) is a 3-bedroom, 2 bathroom, detached single-family home.

Currently, we have a lot of singles and couples living with roommates, because our most common housing type doesn't work for our most common household type.

Families will benefit from singles and couples moving to 1br apartments, by virtue of the pre-existing family-style housing returning to family use. (This isn't just suburban, either, over half of LA, Seattle, and other major cities is zoned single-family)

There's a whole housing market, and new housing isn't the only type to take into consideration.

"This makes families unable to profit from the recent boom in urban housing."

ReplyDeleteHere's where I disagree.

The most common household size in America is a single person.

The most common (accounting for a plurality and about 40% of all units) is a 3-bedroom, 2 bathroom, detached single-family home.

Currently, we have a lot of singles and couples living with roommates, because our most common housing type doesn't work for our most common household type.

Families will benefit from singles and couples moving to 1br apartments, by virtue of the pre-existing family-style housing returning to family use. (This isn't just suburban, either, over half of LA, Seattle, and other major cities is zoned single-family)

There's a whole housing market, and new housing isn't the only type to take into consideration.

According to Census data in https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/families/2019/cps-2019/tabavg1.xls, the most common type of household is the family, at nearly twice as many family as non-family households. The average size of a family household is 3.21; the average size of a non-family household is 1.25.

DeleteAnecdotally, I have never had a problem, in two geographically distinct markets, in two different flyover country states, finding apartments with 1Br units to live in. While I don't necessarily have an extensive social network, I've never known any other single people who needed to band together because there were no such units available anywhere in the market. There's certainly some geographic sorting because of zoning; but apart from situations where I've seen single family neighborhoods bought up by absentee landlords who rent to groups of college students, i.e. outside speculation, I've never witnessed any concerted pressure on family homes by non-family households. I'll take your word that that's a thing in specific parts of Seattle, or San Francisco, or wherever the geographic sorting forces singles out of the neighborhoods they otherwise want; but not nationwide, where desirability is more dispersed.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteGenerally, the larger footprint is dictated by the desire to put structured parking on one or more levels of the building. Zoning requirements in my city are for a 62' (19 m) parking bay, with a 24' aisle bounded by two 19' parking lanes. Some cities require 64' (20 m). Recent apartment construction in my city is as deep as 22m, with parking underneath, and not surprisingly, it's all studios and one bedrooms. The one I'm referring to is built as part of a transit center. Other newer housing accommodates larger units in buildings only 15 m deep, with parking provided on street, in courtyards, or in nearby garages.

ReplyDeleteThe argument that this large footprint is dictated by structured parking underneath is an interesting one, but it seems to me that it's based on an incorrect assumption... namely, that you have to maintain the same footprint size for every level of a building. Why can't the level with the parking be bigger than the levels above with residential units?

DeleteI posted a new post where I explained my own theory as to why we see these huge buildings. Namely, development revenue is proportional to floor area built, and if floor area is not controlled directly by regulation, then developers have an economic interest in filling up all the space they are legally allowed to build in. My solution is to make sure that there is a FAR limit that is less than the total space that geometric regulations (setbacks, margins, height limits) allow.

Indeed, in the city I went to college, the parking is often on the ground level and extends to the end of the properly line while the building itself is set back.

DeleteI was going to say that buildings in my former college town (Waterloo, Ontario) are generally narrower than this, until I read up to the part where you said multiple bedrooms require more units.

ReplyDeleteWell yeah, the buildings in Waterloo were largely built for students, and many of the units have 4-5 bedrooms. This is in large part due to a different zoning incentive, requiring 1 parking space per unit. The walkability and transit is quite good for a city its size, so car ownership among these students is quite low. Since zoning allowed apartments with to 5 bedrooms, developers decided to maximize bedrooms per unit to minimize parking per bedroom.

Since many of the buildings were built in formerly SFH areas, assembling large lots was relatively difficult anyways, so we got a lot of narrow buildings like these, usually with a pair of 4-5 bedroom apartments per floor.

https://www.google.ca/maps/@43.4772337,-80.5372683,3a,75y,252.58h,102.97t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sPrDdyd_RqY3FEbfXP9YaeQ!2e0!7i13312!8i6656

Or when two lots were combined, you'd get square shaped buildings with four corner units per floor like this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=162&v=U6191_q26QE&feature=emb_title

In the last few years, there's been some zoning changes. Now it's 0.2 parking spaces per bedroom, rather than 1 space per unit. Higher densities are also allowed in more areas near the universities. So we're getting more smaller units and more buildings with larger and wider footprints, but I'd say that the floor-plates are still smaller than in Toronto. Although they aren't really building 4-5 bedroom units anymore, there's still a lot of 2-3 bedroom units being built.

To be honest I think the causation is the wrong way around.

ReplyDeleteThere is so much pent up urban demand for dense living in the US that one could conceivably build a building full of studios and make the most money that way, and then developers figure out which building form will fit the most studios.

The underlying issue is that there is still nowhere near enough supply for urban living, and generally speaking three or four studios or 1-bedrooms will fetch higher profit than a 3-bedroom, so that's what's getting built. A better solution would be to increase buildable land supply, and through the virtue of building to meet demand, eventually the premium will vanish and people will start building normal family apartments again, as used to be common.

It'll be interesting to see what happens in places getting rid of SFH; maybe we'll see more multi-bedroom apartments if 1-bedroom demand is getting met adequately elsewhere.

I think we have to be careful, because causality feedback loops in urban planning and economics are very common (A affects B which affects A, etc...). If there is enough demand for singles' housing that results in buildings full of studios and 1-BR apartments being viable, then ok, but the problem is that buildings with this type of housing can generally better use the available space and be built at a higher FAR while respecting setbacks, height limits and required margins.

DeleteThe problem is that land prices are, to my understanding, proportional to the amount of floor space that can be built. So because these buildings are built, this affects land value and makes other types of building more expensive.

For example, if you can build an obese building full of studios and get 100% FAR, but if you built more family-friendly units, you'd be limited to something with 80% FAR because you have the same height limit and you need to make the building less thick, then the land value per square foot of the latter building will be nearly 25% higher because speculators will demand to be paid as if the most economically viable building was being built (the thick one with studios.

If you live in a major city where the average square foot of floor area is 500$, and 300$ of that is just the land value, then that increases the cost of family-sized units from 500$ to 575$ per square foot. For someone looking for a 800sf unit, that mean 460 000$ instead of 400 000$... and that's if the developer doesn't seek to recoup the lost profit margin, which may push prices even higher.

So if we regulated FAR more strictly and building dimensions and shape less(or controlled area to perimeter ratios), that problem would not happen, because building something with only studios and 1-BR apartments would not increase FAR nor profit margins. So we'd be on a level playing field, allowing developers to build a higher diversity of housing typology... AND allow existing buildings to be more easily adapted in case of market shift.

I think the focus on zoning setbacks and height limits isn't quite right. The most likely cause are the fire codes and internal layouts.

ReplyDeleteAlmost all of the North American examples are double-loaded buildings with a central hallway and units on either side. I wouldn't be surprised if the european examples have units that extend through the building - which is a lot trickier to do if you have to meet the US egress standards (often - and elevator and two separate stairways).

This post is focused on high rise floorplates, but it shows how the specifics of the code shape the building: https://letsgola.wordpress.com/2015/02/09/high-rise-codes-housing-affordability-in-los-angeles/

You can have thinner buildings or buildings with different shapes while having a double-loaded building and respecting fire codes. But to do this would require a reduction of buildable FAR within the confines of the buildable geometric as defined by height limits and setbacks.

DeleteIf we modified regulations so that FAR was the bottleneck, not geometric rules, then I think it could free developers to attempt more building shapes to create housing units that have better ventilation, access to sun and the ability to have more bedrooms without becoming much bigger (and more expensive).

Do you have a source on the bits about windows and sun? Even just more insight into the intuition for them? This seems like one of the major bottlenecks to density and I'd like to understand more about it and what housing would look like optimized for high FAR with this in mind. It seems like there'd be a distribution of effect on people from little sun, etc, and that a system allowing the market to capitalize on those unaffected would be nice. For example, how does Paris make do with 6 floor buildings and tiny streets? Would it work with 10 floors and not significantly more street? 20 floors? 40? The logical limit of your high FAR designs with windows is just a bunch of regular tiny columns of outside brought into a huge building the size of a block. Japan has the Shadow Restriction and urban design guidelines detailing slanted geometry limits; doesn't it seem like there are easier ways to accommodate this?

ReplyDelete