The debate on housing affordability is a big one currently, and I've written a lot on it. There are essentially two sides from what I can see: those who believe that the only way to get house prices in urban neighborhoods down is to increase supply, ie build more units, and those who believe that supply has little to do with prices, that allowing more density might end up disturbing the community and destroy neighborhoods as they are, who instead favor rules to keep prices down through rent control and the like.

Much of the debate goes around supply and new constructions. One side says "build more", the other says "building more doesn't help".

Now, overall my sympathies are clearly with the first camp, supply is extremely relevant to prices. However, I think it's important to underline that just allowing new constructions will not be sufficient to lower prices. There is another factor that is just as important: the marginal cost of housing, how expensive is is to add new units.

First, an analogy, the price of oil

First, a simple analogy. Let's take oil and suppose there are two types of oil well available. One has oil that is easy to extract, the costs of doing so actually mean that you can sell the oil from it for 60$ a barrel for a reasonable profit, but the production of the well is limited to 10 000 barrels a day. The other source is actually oil sands, which are much more expensive to produce, to make a profit, you need to sell every barrel at 120$. This well also has a maximum output of 10 000 barrels a day. Now, in reality it is more complex than that, but I'm just illustrating an example.

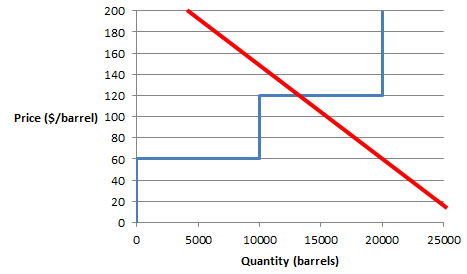

Okay, so here is what the supply curve would look like:

|

| Supply curve for the oil example |

What this means is that below 60$ per barrel, no oil is going to be produced as it would not be profitable. There is no source of oil that could be tapped for such a low price. It's only when people start being willing to pay 60$ per barrel of oil that the first well will be tapped. Now, let's add a demand curve to the graph for an hypothetical demand level.

|

| First case scenario |

What this demand curve means is that if the price of oil was 0$, people would be willing to buy 12 000 barrels per day, if the price was 100$, no one would buy any. At 60$, people are willing to buy 5 000 of them. So if the equilibrium is reached, it would mean that the well owner would pump out 5 000 barrels a day and sell them at 60$ a day. If they pump out more, they won't be able to sell them, if they pump less, they will not sell as many as they could and would have shortages. Okay, if they were a monopoly, they could ostensibly do that, but let's presume perfect competition that precludes this idea.

Now let's say that, with time, demand increases, the demand curve moves up, and now, at 60$, people would actually use 13 000 barrels of oil, more than what the first well can provide.

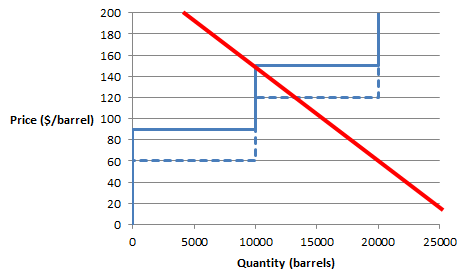

|

| Second case scenario |

The problem is that the maximum amount of oil that can be produced for a price of 60$ is 10 000 barrels, and no more. You can increase production, but each barrel would require a price of 120$ to be profitable. So producing oil at that price would bankrupt people. The result is that the equilibrium will be reached at a price of about 90$, for a production of 10 000 barrels of oil. So as demand increases, so will prices, while supply will remain the same.

Once the amount of oil people will buy at 120$ exceeds 10 000 barrels, the second well will be tapped, and then supply will increase. But though supply increases, prices will not go down below 120$. If they threatened to, production at the second well would stop as it would no longer be profitable.

|

| Third case scenario |

Here, oil consumption will be 13 000 barrels per day, at 120$ per barrel.

Now, some hypotheticals....

What happens if some new technology allows the exploitation of the second well at lower prices, say 90$ per barrel?

|

| Third case, hypothetical 1 |

So here, oil becomes cheaper and there is more of it consumed and produced. The amount of oil produced is increased from 13 000 to 17 000 and the price is lowered from 120$ to 90$.

What happens if, on the other hand, in order to reduce oil consumption there is a 30$ levy on all oil barrels produced? A levy that increases cost of oil by 30$, no matter from which well it comes from?

|

| Third case, hypothetical 2 |

Here, oil becomes more expensive and there is less of it being produced and consumed. Just 10 000 barrels per day at 150$.

Finally, what happens if the environmental consequences of the second well's production are judged too damaging and the exploitation of the well is banned?

|

| Third case, hypothetical 3 |

Well, here the supply of oil is capped at 10 000 barrels per day. Oil becomes rarer and more expensive, and as demand increases, it will just get more and more expensive all the time and just 10 000 barrels per day will be produced and consumed.

So, back to housing...

Housing works a bit the same way. Of course, the first rule of analogy is that no analogy is ever perfect, oil is oil, but a McMansion isn't a studio apartment. Yet, the lessons from the analogy holds I think.

Instead of oil, suppose that the previous graph was housing, the cheaper oil is like the greenfield developments: when there are plenty of vacant lots which are available to build low-rise wood-framed building. The maximum output of that well is the amount of such housing you can build before you run out of vacant lots to build them on. The second, more expensive well is infill development: tearing down low-density housing and building denser, taller housing instead, which is more expensive because you need to incorporate the cost of the previous housing in the cost of the new housing and the taller you build, in general the more expensive the building is per square foot.

Instead of oil, suppose that the previous graph was housing, the cheaper oil is like the greenfield developments: when there are plenty of vacant lots which are available to build low-rise wood-framed building. The maximum output of that well is the amount of such housing you can build before you run out of vacant lots to build them on. The second, more expensive well is infill development: tearing down low-density housing and building denser, taller housing instead, which is more expensive because you need to incorporate the cost of the previous housing in the cost of the new housing and the taller you build, in general the more expensive the building is per square foot.

Anyway, if you want to bring down housing prices, it doesn't suffice to allow more construction, you must make sure that this new construction is affordable to build. If the new units are too expensive to build, supply may still increase, but the price may not go down by much, if at all. Housing prices would simply be lower than they would be if you banned that development, but not cheaper overall.

Much of the time, no one is more hated than the developer, and people want to make him pay for daring to change the neighborhood. He will be made to jump through hoops, to make his case before committee after committee, eager to extract concessions out of him, in certain instances, neighborhoods and authorities will demand little less than bribes out of him: for instance, want to buy a condo tower there? Okay, but build us a public park on one part of your land. So the entire neighborhood has a park... paid for by the few people who will have bought one of the new condos.

In fact, this is often portrayed as a "compromise" between the two sides of the supply debates: we're going to allow some more supply, but we're going to control it and demand concessions in exchange.

All of these drive up the price of building new units and makes sure that the only units that developers can build for a profit are luxury units. To go back to the analogy, it's like you just put a huge tax on oil, making it more expensive to extract, the result would be less oil and more expensive oil... just like piling on development costs on new housing results in less housing and more expensive housing.

So if we are serious about housing affordability, I think what is required is:

-More "as-of right" density allowed

-Minimal revisions from planning offices and city planners and an expedited approval process

-Not imposing excessive taxes and charges to developers, only the minimum to pay for the development's direct cost to the community

The harder we make it to build new housing stock, the more expensive and high-end this housing is going to be. As a further consequence, since existing housing has to compete with new housing, the more expensive new housing is, the more expensive existing housing will get.

The case of imposed affordable housing

In certain cities, they have started to demand to developers to build affordable housing that will be most sold at under-market prices in new developments, essentially using the market-rate units' profits to subsidize certain units. That's the kind of idea that do add some cheaper units, but at the cost of creating an imbalance. Since the market-rate units are forced to include as a cost part of the cost of "affordable" units, it means that the cost of building units is even higher. It's not a solution in and of itself, because the higher cost of the market-rate housing will make it too expensive to build except for extremely high luxury units, of which fewer can be built because there is less demand for them.

No comments:

Post a Comment